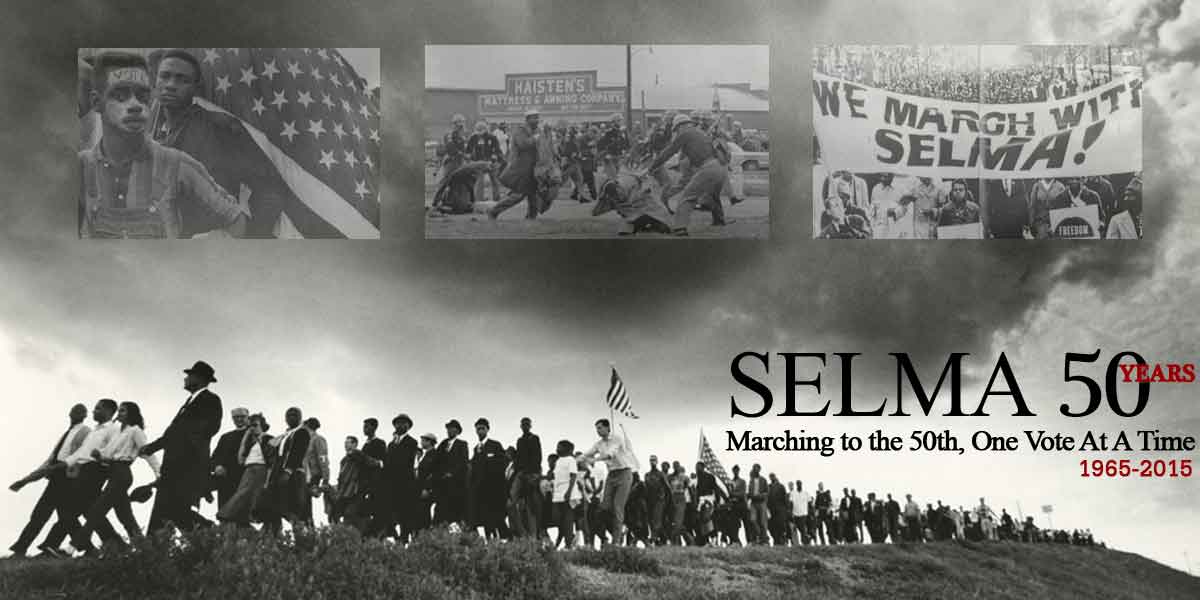

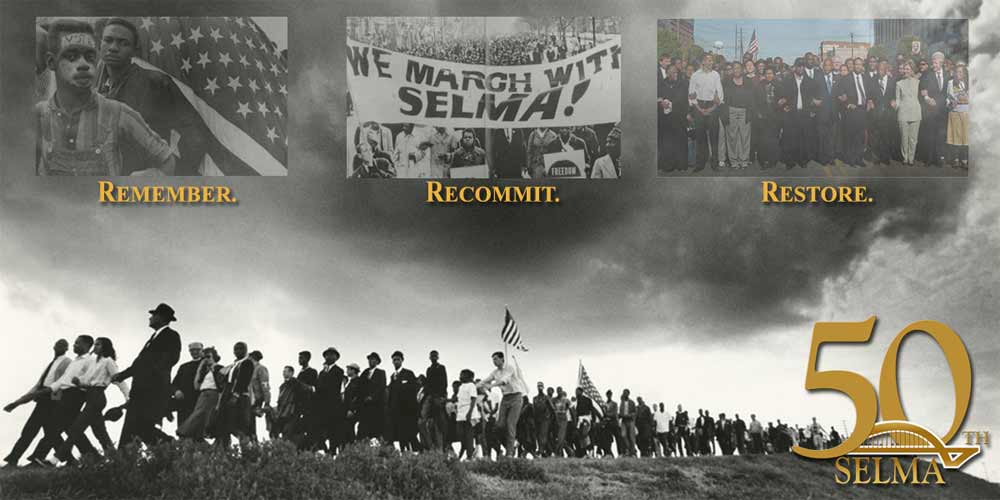

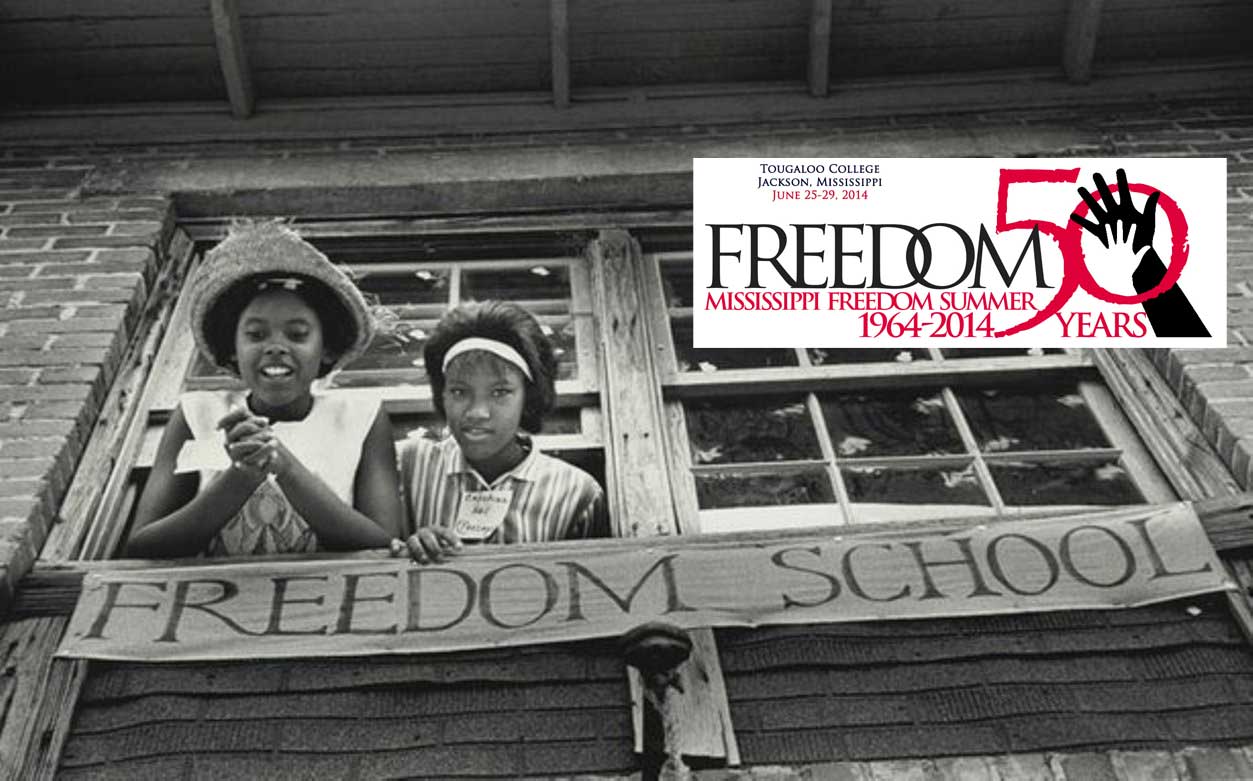

The Mississippi Freedom Summer 50th Anniversary Committee convenes the Freedom 50 Conference June 25-29 at Tougaloo College in Jackson, Mississippi, to celebrate the civil and human rights accomplishments of brave activists who combated segregation in 1964 and developed strategies that continue to improve the lives of Mississippians and the rest of the country.

In 1964, key civil rights organizations including the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), the Congress on Racial Equality (CORE) and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference coordinated the Mississippi Summer Project, or Freedom Summer, to dramatically increase Black voter registration in strictly-segregated Mississippi where white supremacy, “the Southern way of life,” was viciously enforced. Young activists registered black voters, established citizenship schools to teach financial literacy and civic engagement, among other things, to help Blacks who struggled under generations of institutional racial oppression and resulting poverty.

“These volunteers and workers risked their lives, some of them even lost their lives, fighting for equality and justice during the Freedom Summer Project of 1964,” said Hollis Watkins, National Chair for Freedom 50. “All of these honorees changed my life and the lives of many others. Their work not only impacted Mississippi, but also helped the nation to open its eyes and look at itself. We are fighting old battles today and that’s why Freedom Summer 50th is so important. We are deeply grateful to honor and recognize these freedom fighters.”

The Mississippi Freedom Summer 50th Anniversary Committee will convene the Freedom 50 Conference June 25-29 at Tougaloo College in Jackson, Mississippi. The conference convened by the Veterans of the Mississippi Civil Rights Movement, Mississippi State Conference NAACP, One Voice and Tougaloo College celebrates the accomplishments of those who who combated segregation in 1964 and developed strategies that continued to improve the lives of Mississippians and the rest of the country. The conference includes workshops on issues of education, voting rights, workers’ rights, and health care to explore the continuing struggle toward the day when all Mississippi citizens reach their full potential.

The Mississippi Freedom Summer 50th Anniversary Committee will convene the Freedom 50 Conference June 25-29 at Tougaloo College in Jackson, Mississippi. The conference convened by the Veterans of the Mississippi Civil Rights Movement, Mississippi State Conference NAACP, One Voice and Tougaloo College celebrates the accomplishments of those who who combated segregation in 1964 and developed strategies that continued to improve the lives of Mississippians and the rest of the country. The conference includes workshops on issues of education, voting rights, workers’ rights, and health care to explore the continuing struggle toward the day when all Mississippi citizens reach their full potential.

Commemorative events around Mississippi’s Freedom 50 includes several exhibits

Commemorative events around Mississippi’s Freedom 50 includes several exhibits

and a film festival that includes airing of the documentary, Freedom Summer, produced and directed by MacArthur Foundation “genius grant” recipient, filmmaker Stanley Nelson. It gives a glimpse of the difficulties Mississippians went through in the summer of ’64 in the struggle for equality and justice for all. The efforts of the Freedom Summer volunteers helped to shape what Mississippi looks like today. Presently, the state has more African-American elected officials than any other state in the country.

The Freedom 50th celebration culminates with the Legacy and Recognition Banquet, honoring those who organized, led and volunteered in Mississippi’s Freedom Summer project 50 years ago. Tickets are $100 and tables of 10 are $1,000. For sponsorship and ticket/table information, please call (601) 977-7914 or email msfreedomsummer50th@gmail.com. Tickets may also be purchased online at www.freedom50.org/registration through June 20th.

“Freedom Summer was a significant event in the history of not only Mississippi, but in America,” said Derrick Johnson, Freedom Summer national co-chair. “It opened up an alliance in ways in which all Americans can fully participate. We want to honor that movement by asking people to come back and celebrate not only the successes of Freedom Summer, but also begin a new discussion on how to secure democracy for all citizens of this country.”

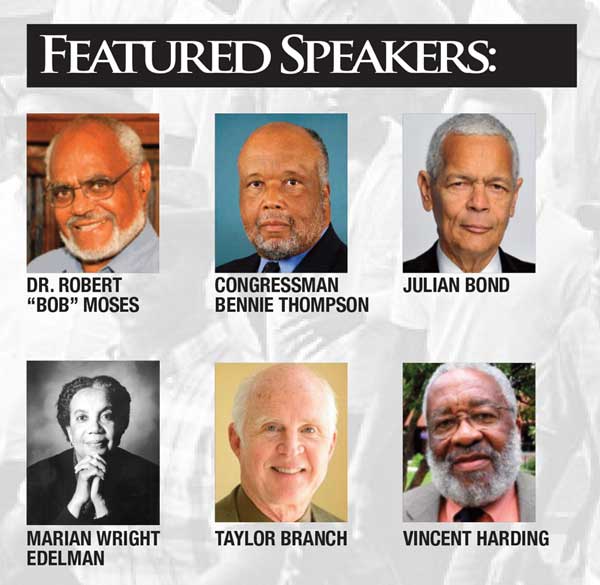

- Dr. Robert “Bob” Moses, project director of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) in Mississippi from 1961-65 and a principal organizer of the 1964 Freedom Summer Project and is currently director of The Algebra Project;

- Julian Bond, a founding member of the SNCC who served as its communications director 1961-66, and personally led student protests against segregation in public facilities in Georgia;Congressman Bennie Thompson, SNCC member who helped organize voter registration drives for African-Americans in the Mississippi Delta;

- Dick Gregory, comedian and civil rights activist who used his celebrity to raise funds to support civil rights activities across the South during the ’60s and continues to be an outspoken human rights advocate;

- Marian Wright Edelman, founder and president of the Children’s Defense Fund (CDF), who began her career in the mid ’60s when, as the first black woman admitted to the Mississippi Bar, she directed the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund office in Jackson, Mississippi; and

- Taylor Branch, author and public speaker best known for his landmark narrative trilogy of the civil rights era, beginning with his first book, the Pulitzer-prize winning Parting the Waters: America in the King Years, 1954-63, along with the two other critically-acclaimed books, Pillar of Fire: America in the King Years, 1963-65, and At Canaan’s Edge: America in the King Years, 1965-1968.

See more about the conference and other event details online at Freedom50.org

Historical Significance

In the 1960s, civil rights workers in Mississippi organizations struggled to register voters as part of the African American struggle to enjoy the full rights of citizenship denied since the end of the Civil War, despite constitutional amendments that guaranteed their rights. This systematic denial of Black voting rights was replicated across the Black Belt areas of Louisiana, Alabama, South Carolina, and Southwest Georgia. But it was particularly vicious in Mississippi.

In 1961, at least 41 percent of the state’s population was Black, but 5 percent of the its eligible black voters were registered to vote. In many of Mississippi’s Black-majority counties not a single African-American citizen was registered, not even decorated military veterans. In urban areas of the Deep South, a few token Blacks — usually ministers, teachers, doctors, and other professionals — were allowed to register, but never enough to affect the outcome of an election. Only a few of those who actually made it onto the voter rolls dared to actually cast a ballot. Whites used rigged “literacy” tests, white-only primaries, poll taxes, arrests, and economic retaliation to suppress the Black vote. They often resorted to violence through the Ku Klux Klan, which even used assassinations of key black leaders to maintain Mississippi’s southern way of life despite federal laws.

In 1961, at least 41 percent of the state’s population was Black, but 5 percent of the its eligible black voters were registered to vote. In many of Mississippi’s Black-majority counties not a single African-American citizen was registered, not even decorated military veterans. In urban areas of the Deep South, a few token Blacks — usually ministers, teachers, doctors, and other professionals — were allowed to register, but never enough to affect the outcome of an election. Only a few of those who actually made it onto the voter rolls dared to actually cast a ballot. Whites used rigged “literacy” tests, white-only primaries, poll taxes, arrests, and economic retaliation to suppress the Black vote. They often resorted to violence through the Ku Klux Klan, which even used assassinations of key black leaders to maintain Mississippi’s southern way of life despite federal laws.

President John F. Kennedy and federal authorities plans to tame the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s crashed into the rock of staunch racist resistance. The South’s white power-structure was even more furiously — violently — opposed to Blacks gaining the right to vote than they were to desegregating lunch counters and bus stations. Instead of diminishing, the news stories of brutality, bombings, and murders increased as the Klan and White Citizen Councils used every form of terrorism and economic retaliation to prevent Blacks from voting.

This organized and violent racial opposition to Black voting rights in the South, and in Mississippi particularly, was so ferocious, so violent, and so widespread, that only by uniting all of the state’s civil rights organizations into a coordinated effort was there any hope of success.

The 10-week Freedom Summer Project was the collective work of several activist groups that came together under the Council of Federated Organizations (COFO), composed of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), and Mississippi local units of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), with legal support from several national legal groups, medical support from Medical Committee for Human Rights (MCHR) and local churches across Mississippi.

The 10-week Freedom Summer Project was the collective work of several activist groups that came together under the Council of Federated Organizations (COFO), composed of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), and Mississippi local units of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), with legal support from several national legal groups, medical support from Medical Committee for Human Rights (MCHR) and local churches across Mississippi.

We were a band of sisters and brothers, a circle of trust. …

We were young.

We had energy.

We had brains.

We had technical skills.

We had a belief in people and their power to change their lives.

We were willing to work with the most dispossessed — the sharecropper, the day laborer, the factory workers, and the mill hands.

We were not afraid of death.[1] — SNCC Executive Secretary James Forman

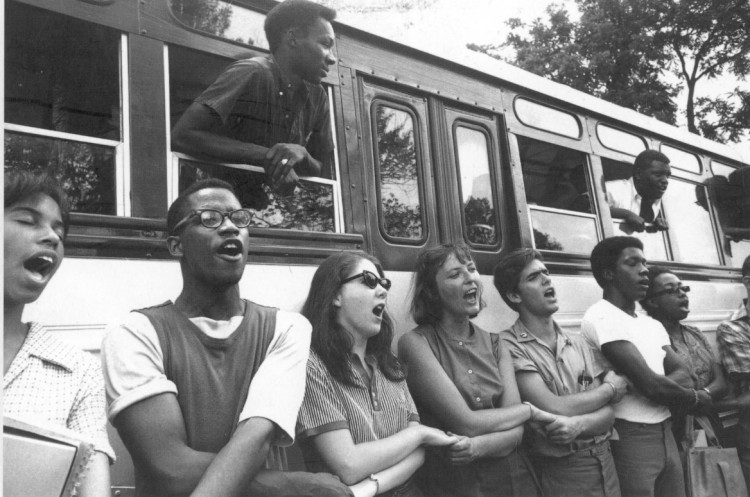

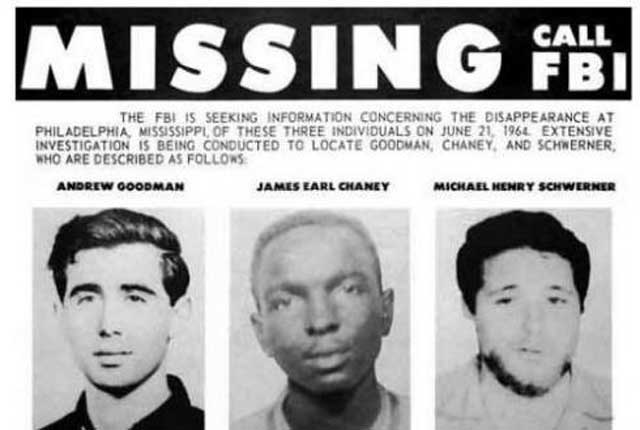

The coalition was comprised of veterans of the 1961 Freedom Rides, black Mississippians and more than 1,000 out-of-state, predominately white volunteers, who all faced constant abuse and harassment from Mississippi’s white population. The Ku Klux Klan, police with local and state local authorities carried out a series of systematic violent attacks on the young activists including arson, beatings and false arrest. Three of them — Michael Schwerner, James Chaney and Andrew Goodman — were killed in what became known as the “Mississippi Burning” case.

Despite external violence and internal pressures of group and racial dynamics, the activists persisted in their voter registration and education efforts, though the rolls didn’t swell with hundreds of thousands of new Black voters, and federal help came only after the Voting Rights Act of 1965. However, the project awakened many Black Mississippians to their power to change their condition. Some residents later became leaders in their state and across the country, like Fannie Lou Hamer.

Nobody had to say that all of us were equal; we could feel it. These were the first moments of my life when I knew that people outside my family respected me for what I knew and what I had to offer. They wanted to know my ideas, to get my advice about what they should do. I was telling them what to do. . . . I had been beat way down, and the realization that I had something of value to give someone else was a powerful sensation. At the time I didn’t even know how to describe it, but it gave me strength. — Unita Blackwell. [7]

Sources: Historical information from the Civil Rights Movement Veterans website, http://www.crmvet.org/tim/tim64b.htm#1964fsfs. News information culled from the Jackson Free Press, The Times Democrat and the Associated Press.