Fifty years ago yesterday marked the beginning of what historians call “The Children’s Crusade,” when several thousand African American students took to Birmingham’s streets during the 1963 Birmingham Civil Rights Campaign.

Fifty years ago yesterday marked the beginning of what historians call “The Children’s Crusade,” when several thousand African American students took to Birmingham’s streets during the 1963 Birmingham Civil Rights Campaign.

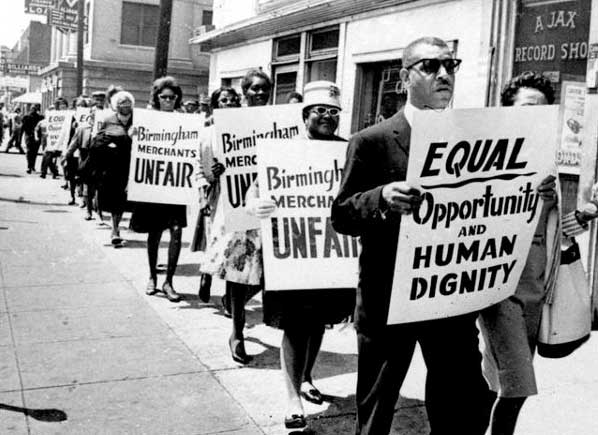

The springtime campaign, dubbed “Project C” (“C” stood for “confrontation”) was the brainchild of local and national civil rights leaders. They intended to create so much negative publicity and economic tension on Birmingham’s white power structure that its leaders would feel pressured to meet the black community’s righteous demands for human dignity, basic fairness in society and equal treatment under the U.S. Constitution (not local, racially discriminatory laws).

The springtime campaign, dubbed “Project C” (“C” stood for “confrontation”) was the brainchild of local and national civil rights leaders. They intended to create so much negative publicity and economic tension on Birmingham’s white power structure that its leaders would feel pressured to meet the black community’s righteous demands for human dignity, basic fairness in society and equal treatment under the U.S. Constitution (not local, racially discriminatory laws).

Dr. Martin Luther King’s powerful 7,000-word “Letter for Birmingham Jail” states the rationale behind why those civil rights leaders did what they did far more eloquently than I can in so short a space.

King’s eloquence stirred the hearts of people oppressed for generations under brutal and inhumane racial segregation, particularly in Birmingham. His words moved them, even children, to action. His team of young lieutenants sought and taught willing students the methods and rationale for strategic (nonviolent) action. And masses of them executed the planned action with divine purpose.

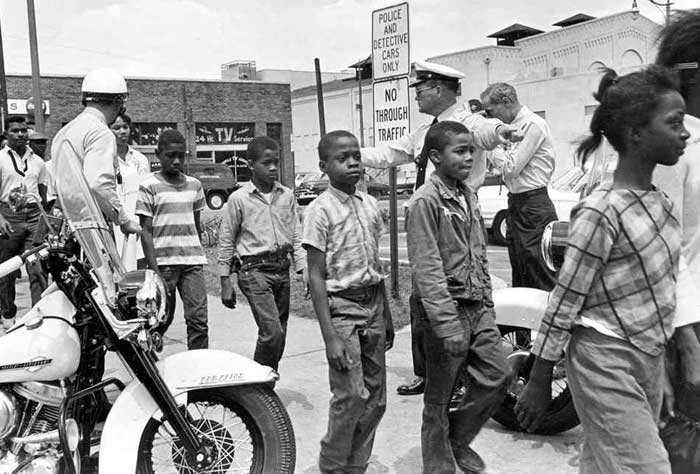

So from May 2 – 7, 1963, the vast majority of the masses who crowded Birmingham’s streets were high school students; other schoolchildren were as young as seven and eight years old. Many were arrested; city jails overflowed. Some children were locked up at the state fair grounds’ open-air animal stockade where they were rained on.

What in the world could have motivated these children to do something so crazy and dangerous, to endure jailings, to face  pressurized fire hoses that could cut away clothes and skin, and police dogs that could rip flesh?

pressurized fire hoses that could cut away clothes and skin, and police dogs that could rip flesh?

Talk to any of these now-grown students, and they’ll tell say one word that succinctly encapsulates the vision Dr. King and his lieutenants conveyed to them: Freedom.

Freedom to eat, shop or live where they wanted. Freedom to go to any bathroom instead of the one for “coloreds,” which were often foul and unkempt. Freedom to sit anywhere they wanted on a bus, at an airport or train station. Freedom to go into any movie theater. Freedom to try on clothes before buying them. Freedom to pursue jobs and any economic endeavor to attain the American Dream and live as any other white middle-class American was free to do.

These things sound ho-hum common, no big deal, to our modern ears, especially to today’s children. But 50 years ago, these notions of freedom for the average African American child were radical, even “Communist.” A black person of any age who aspired to achieve this kind of freedom, particularly in the South, was “uppity” and had forgotten his or her “place,” an unequal and degrading second-class (or no-class) citizenship. And every societal system – criminal justice, education, commerce, government, healthcare, and culture in general – was engineered to suppress even the thought of freedom so that blacks were artificially locked down in this subordinate class of humanity.

The simple thought of freedom, to live as fully as any white American (or human being, for that matter), is what motivated these black children. “It was simple things like this that sparked our imagination and made us want to march,” says Brenda P. Hong, who left Western-Olin High School with hundreds of other students in May 1963.

The simple thought of freedom, to live as fully as any white American (or human being, for that matter), is what motivated these black children. “It was simple things like this that sparked our imagination and made us want to march,” says Brenda P. Hong, who left Western-Olin High School with hundreds of other students in May 1963.

Their hunger and thirst for justice and fairness — starved as they were in the perverse system of racism — made Dr. King’s call for disciplined, nonviolent action easy to answer. But being children, they didn’t understand the depths of depravity that some people in power can exhibit when they perceive their power is threatened.

Shirley Holmes-Sims recalls one of her classmates saying that firemen under the watch of then Police Commissioner Eugene “Bull” Connor had intentionally trained their high-powered hoses on Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth, the fiery local civil and human rights leader known nationally as the Movement’s most fearless combatant. The water’s force knocked him down the steps at Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, cut his clothes and might have killed him if one fireman had not put a stop to the madness.

She too had felt the water’s sting; it felt like a knife cutting her leg. And that was from water deflected off another student who was in the mass of students who marched that day.

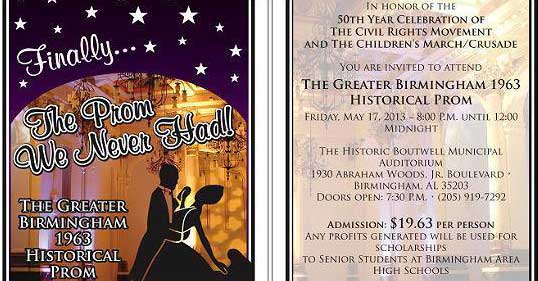

Holmes-Sims, Hong and other students who marched paid a heavy price for participation in the Movement: school officials expelled them and cancelled black schools’ prom. The punishment for participation was devastating at a time in black society when graduation was a source of great community pride, and the prom was a highly important rite of passage.

Civil rights lawyers got the students re-instated, but the Class of ’63 never got a prom. But these ladies and others formed a small committee to host “The Prom We Never Had” later this month (see Sherrel Stewart’s excellent article in The Root, which will run in The Washington Post on Friday).

But these ladies are having trouble raising money and other support for this wonderful event. And this bothers me deeply.

Every black person and institution in this city should get behind this event because the students of ’63 who participated in the Birmingham Movement opened doors for us that might likely still be shut in our faces. Every citizen – black, white, brown, yellow, blue or purple – owe these people a debt of gratitude because they made our democratic nation fairer and more just for all.

But what troubles me more is the rampant ignorance about the nature of Birmingham’s civil rights history – why the demonstrations were necessary, what precipitated such drastic and heroic action, its deeply spiritual dimensions, and what lessons it holds about how we address current civil and human rights problems. Birmingham’s history is not systematically taught in city schools. Some students at yesterday’s re-enactment of the Children’s Crusade didn’t know about the history they watched in the documentary, “Mighty Times: The Children’s March.” Some did.

As adults we’ve forgotten Dr. King’s lessons (if we ever learned them at all). And yesterday’s elders have failed to pass the baton to the next generation of children, who today have no idea that they are part of a continuing saga, responsible for shaping the next phase of the Movement. These failures are costing us dearly.

Read the complete blog post at Birmingham View Blogs.