When Dorothy Walker found the building on Miles College’s campus in Birmingham, she turned to her intrepid co-explorer, giddy as a gold prospector.

Matching it with a picture from a Fisk University database, she confirmed that the Miles College resource center was in fact a Rosenwald School. It is one of the few remaining testaments to an ambitious and far-reaching school building project in American and African American history.

“I can’t begin to put into words how excited we were when we came to this building and matched it,” Walker, a preservationist with the Alabama Historical Commission, said of the day she first personally found a Rosenwald School in Alabama. She’d been looking for it with Birmingham Public Library Archivist Jim Baggett. “We were both so elated. It was like finding lost treasure!”

However, the significance of their find was lost on the people still using the building.

That is what the organizers of this week’s conference at Tuskegee University hope to change.

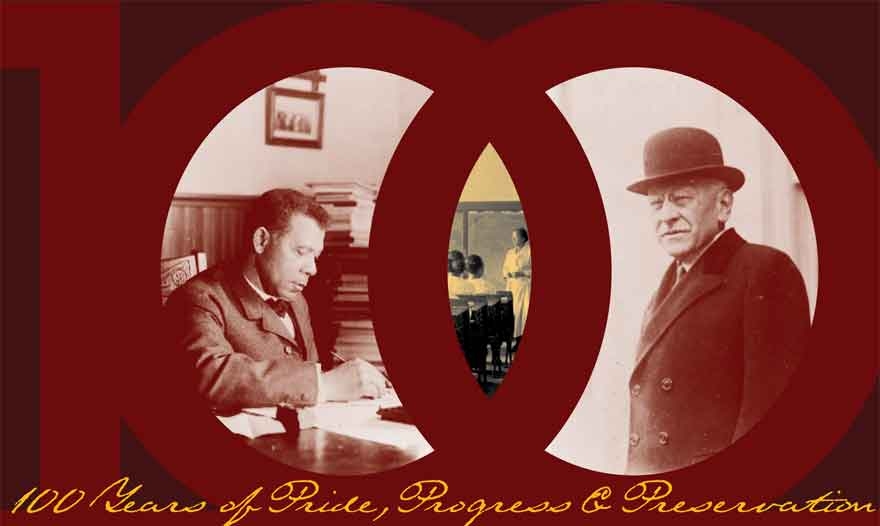

“100 Years of Pride, Progress & Preservation: The National Rosenwald Schools Conference” is a major, 10-year initiative of the National Trust for Historic Preservation to find and save remaining Rosenwald School buildings that were once the pride and community hub of African American communities across the South. Through their own hard work and sacrifice, impoverished blacks leveraged a millionaire philanthropist’s gift to construct thousands of schools and build the best education system they could for their children, despite the brutal hardships of a deeply unfair and unequal society.

Acclaimed poet and author Nikki Giovanni will provide the conference’s closing keynote address.

“This conference provides an opportunity for Rosenwald School alumni and preservationists to share their rich and varied stories, network with each other, and learn more through educational workshops, documentary films, tours and poster presentations to preserve this important part of our nation’s story,” says John Hildreth, vice president of Eastern Field Services for the National Trust for Historic Preservation.

The History

The story begins about 100 years ago, with the savvy Booker T. Washington, head of The Tuskegee Institute, who had pulled himself up from slavery to become a key leader of Black America in the decades following the American Civil War.

In the early 1900s, Booker T. Washington and his staff set out to find private donors to fund black schools in rural areas, first in Tuskegee, then across the South. After building almost 50 schools in Macon County, Washington found a chief ally in Julius Rosenwald, the Springfield, Illinois-born son of German-Jewish immigrants. The savvy businessman helped turned Sears, Roebuck and Co. into a household name and he became its president. He also became a very rich man.

Reading Washington’s book Up from Slavery touched Rosenwald deeply. In 1911, he wrote, “The horrors that are due to race prejudice come home to the Jew more forcefully than to others of the white race, on account of the centuries of persecution which they have suffered and still suffer,” according to his grandson and biographer, Dr. Peter Ascoli.

Rosenwald became a generous benefactor to the African American community both in his hometown Chicago and abroad. In 1912, he began serving on Tuskegee Institute’s board of directors, where he served for life. Rosenwald’s endowment allowed Washington to spend less time traveling to fundraise and more time perfecting his dream of self-help education for blacks.

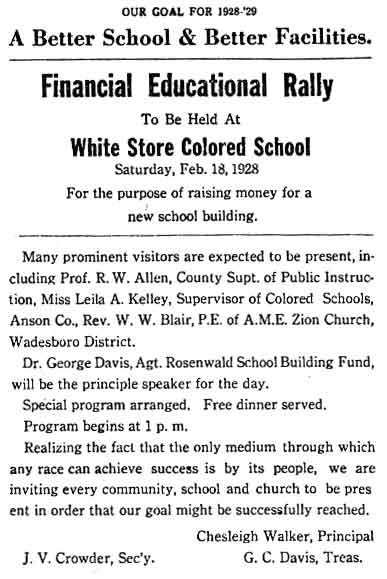

On his 50th birthday, Rosenwald gave the Institute $25,000. Washington asked to use a portion of the gift to build six small rural schools in Alabama. Rosenwald agreed, however he and Washington insisted that local communities raise matching funds to leverage the grant. The first Rosenwald School opened in 1913. Rosenwald was so pleased with the idea and its execution that he provided more funds toward the cost of building more schools. At the time of Washington’s death in 1915, Rosenwald personally gave matching money to fund about 80 schools in three states. He later started the Rosenwald Fund.

As the program grew, architects at Tuskegee – and later the Fund’s program manager – designed state-of-the-art school buildings for the times. The designs had plenty of windows to take advantage of natural sunlight (some rural areas had no electricity). The designs featured moveable walls to turn classrooms into a community meeting space.

take advantage of natural sunlight (some rural areas had no electricity). The designs featured moveable walls to turn classrooms into a community meeting space.

Black schools were grossly underfunded compared to white schools, especially at the turn of the century. The Rosenwald Schools were a vast improvement over the run-down shacks and cramped rooms in stores or churches that black students attended. Eventually , even some poorer white school districts followed the Rosenwald designs, they had become so popular.

Because the Rosenwald grants only covered up to one-fifth of actual construction costs, entire African American communities contributed to the cause. They donated land for schools, grew and sold food, donated supplies, provided free labor to build and maintain the schools, and begged local school boards to provide some public funding. In most instances, Rosenwald School buildings became the civic center of rural black communities, and a source of self-sufficient pride.

The Fund’s school building program ended with Rosenwald’s death in 1932. By then, a total of 5,357 Rosenwald schoolhouses, training shops and teachers’ homes blanketed 883 counties in 15 Southern states from Maryland to Texas and Oklahoma, at a total cost of $28.4 million. The Rosenwald Fund’s donation of some $4.4 million was matched by $4.7 million in black contributions. Local governments spent $18 million, with private white foundations making up $1.2 million. In today’s dollars, the program would have cost more than $300 million.

By 1928, one of every five rural schools for black students in the South was a Rosenwald School. At the first half of the 1900’s, more than a third of Southern black children had been educated in a Rosenwald School. The facilities and the teachers they hired provided blacks of that day with the best education that was available to them and their children at the time.

By 1928, one of every five rural schools for black students in the South was a Rosenwald School. At the first half of the 1900’s, more than a third of Southern black children had been educated in a Rosenwald School. The facilities and the teachers they hired provided blacks of that day with the best education that was available to them and their children at the time.

However, after the 1954 U.S. Supreme Court ruling that banned “separate but equal” schools, black parents abandoned the older Rosenwald Schools, or white public school administrators closed them as integration began.

Historic Preservation Continues

Only 10 to 12 percent of the Rosenwald Schools are left standing; many of those that remain are hazards in danger of collapse. There is the Rosenwald School building at Miles College campus and at least 12 others remaining throughout Alabama.

Generations of African Americans before 1954 have strong memories of overcoming intense obstacles to gain an education, as powerfully symbolized by the Rosenwald School. And they want to keep that story alive for future generations of Blacks. Historians and preservationists want the story told to broader audiences to share the powerful lessons of partnership, how Washington’s dream and Rosenwald’s money created a cross-cultural network of hands that joined together to lift the educational horizons of poor children.

The National Trust for Historic Preservation in 2002 launched a drive to save the remaining Rosenwald Schools, placing them on its list of America’s 11 Most Endangered Historic Places for that year.

This week’s conference will educate the public about the Rosenwald Schools’ history and to provide resources and networking opportunities for groups and towns who have made it their mission to save the forgotten school buildings.

If you or a family member attended a school in the rural south before 1960, chances are, it was a Rosenwald School. If you want to find out if your school or the one your family attended is a Rosenwald School, you can get more information online at http://rosenwald.fisk.edu/.

Conference Information

PUBLIC: To register, or for more information about the National Rosenwald Schools Conference, please visit http://www.rosenwaldschools.com or call (202)588-6407. The public may register for the conference online.

PRESS: Registration for the media is free. ALL PRESS MUST PROVIDE PRESS CREDENTIALS TO ATTEND. For media registration or inquiries, please contact Rebecca Morgan at rebecca_morgan@nthp.org or (202)588-6380. The advance deadline for media registration is May 30, 2012. After that date, media must register on site.

Sources

Rosenwald Schools Initiative, National Trust for Historic Preservation, http://www.preservationnation.org/travel-and-sites/sites/southern-region/rosenwald-schools/

“Schoolhouse: Rosenwald Schools In The South,” by NPR Staff, http://www.npr.org/2012/03/11/148066822/-schoolhouse-the-story-of-rosenwald-schools-in-the-segregated-south

History South: “Saving the Rosenwald Schools,” by Tom Hanchett, http://www.historysouth.org/schoolhistory.html

North Carolina Museum of History, http://ncmuseumofhistory.org/workshops/civilrights1/rosenwald.htm

U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service: National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation form, August, 1997, http://pdfhost.focus.nps.gov/docs/NRHP/Text/64500011.pdf

The Rosenwald Schools Film Project, YouTube Clip

Miles College Rosenwald photo, courtesty of the Birmingham Public Library Archives.