The word “urban” pertains to things associated with cities. In the past several decades, it was a code word associated with ethnicity and lower socio-economic classes. However, urban today has as much to do with a mindset as it does class and geography.

She and her husband were among the very first people to live in the City Center 16 years ago. The City had just changed zoning laws, allowing people to live on second floors in former warehouses and commercial spaces, something that was avant-garde then.

The couple had lived near New York City and in cities such as Minneapolis and Houston, where city living was chic, but not cheap. Upon arriving here, they decided to live in a Vestavia Hills apartment until they could find a place Downtown.

The couple had lived near New York City and in cities such as Minneapolis and Houston, where city living was chic, but not cheap. Upon arriving here, they decided to live in a Vestavia Hills apartment until they could find a place Downtown.

“We had always wanted to have a loft in a downtown, and this was the first place we lived where we could afford one,” Rekoff said. “Also, the last one of our children was in college.”

They found a perfect spot on Second Avenue North, a 25-foot wide, two-story building. They were financially well off, and put down half the money to buy the property. But they couldn’t get a mortgage for the other half because none of the banks had financed a loft then.

So the Rekoffs did most of the renovation work themselves. “We put two years of our lives into this building. It was really hard,” she says of all the permitting issues and bureaucratic red-tape they endured. “We didn’t do it as an investment, but as it turned out, that may be the case. We just wanted to live Downtown.”

Now, about 50 loft apartment and condominium buildings dot the City Center and Midtown, from high-rise and mid-rise historic buildings to smaller owner-occupied buildings. More than two dozen loft developments are underway or planned for Downtown, so hundreds of others are coming.

“It’s night and day,” Rekoff, now a widow, says about the difference between the Downtown residential scene two decades ago and today.

“It’s a wonderful thing. I love all the new people coming in. I tell them, ‘I’ve been waiting for you for so long. Thank you for coming!’ I’m a senior citizen,” the 75-year-old urbanite says with a laugh. “I love all the young kids and all, but now we have people over 30 and 35. And some of my friends over 50 have moved Downtown, and it’s so wonderful.”

Urban, the Remix

Who would buy a Downtown loft condo isn’t easy to define.

“The demographics of Downtown Birmingham are changing,” says real estate agent Chip Watts. “We’re moving away from the Baby Boomers’ concept of a crime-ridden Downtown with vandals and vagrants to a generation . . . who remember how Downtown used to be and a new generation coming in saying, “We want to be urbanites.’”

RealtySouth agent Pete Graphos says his loft buyers are coming from Helena, Homewood, Mountain Brook and other areas. They are affluent, educated and have a different perspective of the City Center than their suburban friends.

One woman’s affluent friends tried to talk her out of buying in “dangerous” Downtown, Graphos says. But speaking to loft residents helped change her mind.

“It’s ironic that the perception of people in the suburbs is that Downtown is not safe when, in fact it’s very safe. And ironically, people are moving in to lofts because of the safety and security factor,” he says. “You can’t get into a building unless you have the code, and in many cases you can’t use the elevator without the code.”

Generally, developers and real estate agents say today’s urban dwellers fit two main profiles.

One includes 40- to 50-something empty-nesters who no longer want to keep up a big house and a yard. The other is the young professional class, either singles or couples, with no kids and an income to take advantage of all that urban living has to offer.

Demographics aside, the new urbanites fit a similar psychographic profile. They love: old buildings with historical character; diverse people of different ethnicities and social backgrounds; the city’s arts and cultural scene and nightlife; the ability to walk or drive short distances to nearby amenities such as restaurants, City Stages, and farmer’s markets.

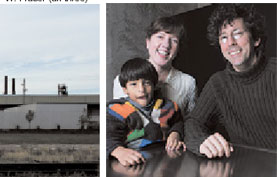

They are like architect Tammy Cohen. She and husband Richard Carnaggio were among the first Downtown dwellers, living for 10 years in a two-story building just down the street from the Rekoffs.

“It appealed to us to be in the City, in a building with tall ceilings and windows, and the character of it all,” she says. “We liked it so much that we bought the building next door for our office. So we were able to live next to our work, which was convenient, because we could walk downstairs to meet clients.”

They eventually outgrew their business space and began looking for another place to have their office downstairs and their home upstairs. The location of their two-story live/work space? On First Avenue South in the Seaboard Yard development.

“Omy-gosh,” Cohen gushes when talking about their new location.

“Omy-gosh,” Cohen gushes when talking about their new location.

“You watch the planes, the trains, the cars, the furnaces. You can see the City lights at night; the sunset is unbelievable! It’s the best view I’ve ever had,” she says. “The trains don’t bother us. It’s quiet indoors. It only gets noisy outside. We’re in

a concrete structure with insulated glass. So the trains don’t disturb us when we’re at home or at work. And our little boy loves to watch the trains.”

Not only have Cohen and Carnaggio seen Downtown Birmingham’s transformation; they are part of it.

Their firm, Cohen Carnaggio Reynolds Architecture and Interiors, has designed several redevelopments such as the Kress Building, home of the Wiggins Childs Quinn & Pantazis law firm.

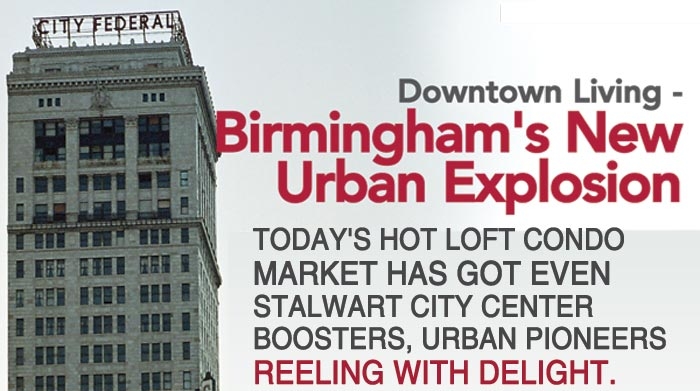

But their biggest and most visible projects will help usher in a new wave of urban living: the $55 million mixed-use (government, commercial, and residential) SoHo development in Downtown Homewood and the $20-million plus loft condo conversion of City Federal in Downtown Birmingham.

“I think the whole move to live back Downtown is upon us like it is in other cities. I think we’re about to reach a critical mass where we have more retail, grocery stores and entertainment for loft dwellers,” Cohen says. “It’s bringing life back to these empty buildings and 24-hour activities and people walking their dogs. Ten years ago, we used to be the only ones walking our dogs. Now we run into many, many neighbors.”

A Whole New World

So Birmingham’s new city dwellers, more simply stated, are more urban than suburban.

“You have a lot of people moving in from out of town who know what downtown living is like and you have a lot of people that are ready for more urban kinds of living,” says Elias Hendricks, a Birmingham City Councilman whose political district is the heart of the new residential district.

He and wife Gaynelle were also among the “urban pioneers” who left their comfortable suburban digs and bought the Transportation Building in 1996. They spent more than $1 million converting it to residential use. Now that the five-year limit has expired on the historic tax credits they used to finance the deal, they are selling off whole floors for more than $400,000, mostly to former renters.

He and wife Gaynelle were also among the “urban pioneers” who left their comfortable suburban digs and bought the Transportation Building in 1996. They spent more than $1 million converting it to residential use. Now that the five-year limit has expired on the historic tax credits they used to finance the deal, they are selling off whole floors for more than $400,000, mostly to former renters.

The Hendrickses are keeping their two-story penthouse perch.

“I think that all of the questions have been answered – is it safe, will the kids have somewhere to go to school and all those things. Are the amenities there? Now, we have nightclubs, restaurants and little art galleries. It’s fun to be down here.”

The black city councilman doesn’t worry about his changing constituency, which once included “the poorest zip code in America.” His district now includes Park Place, Birmingham’s first mixed-income residential development that started with a $35 million federal grant in 1999.

“My district is getting younger, and it’s getting more diverse, economically as well as racially. So I think that’s great,” Hendricks says. “This is the beginning of a whole wave. And we’re building a whole new world.

A Place for Everyone?

Architect Jeremy Erdreich and his family’s development company, Metropolitan LLC, are working on upscale lofts, such as those in the Jefferson Home Furniture building, to meet the demand for high-end urban living. But they have also done their part to ensure people of lower incomes enjoy Downtown’s revival.

Metropolitan’s Phoenix Lofts, along with Park Place, are the only two new residential developments specifically designed to take in households earning moderate incomes or less.

Erdreich says his desire to create affordable units Downtown started early in his career.

After completing college at Yale and Harvard (where his coursework included designing an affordable housing project) and after living in an eclectic New York City neighborhood, Erdreich decided to come back to Birmingham in 1996. He was excited about the growing potential for Downtown’s revitalization.

In his first year back, a developer took him on a personal loft tour. Erdreich asked how much the units were renting for. The developer told him the rents were high enough to make the loft conversion profitable.

“Besides, it’s good we’re charging high rents, because we don’t want to attract the wrong element Downtown,” Erdreich recalls him saying. “I said, ‘What do you mean, “the wrong element?” He said, ‘I think you know what I mean.’ It gave me an eerie, icky feeling.

“After that meeting, it became a priority for me personally to figure how to make urban living more accessible to people with moderate and lower incomes,” he says.

It took Metropolitan LLC several years to assemble enough funding sources and a few more years to convert the 168,000-square-foot former South Central Bell headquarters into the Phoenix Lofts, a $9.5 million project. Funding sources such as Alabama low-income housing tax credits and City HOME funds require that 80% of its 74 units remain affordable for 15 years.

In Birmingham, “lower income” is unfairly associated with negative ../images of poor black people, Erdreich says. In other cities, though, it more often means musicians and other artists, restaurant wait staff and young professionals making median incomes or less, members of the so-called “Creative Class,” he says. Many in that class are Phoenix Lofts residents.

With Birmingham’s hot loft condo market, though, Erdreich says it’s unlikely that developers will build affordable units without some government intervention.

So he worries that the expensive units to soon flood the market will draw too many of the well-heeled and upset the socio-economic balance that’s important for the genuine urban experience.

Erdreich believes that creative people, in all their shapes and forms, are what make an urban community vibrant and successful. They’re the ones who’ll demand cool and cheap entertainment, restaurants and retail stores. “All rich people in one place is not interesting . . . You can go to Mountain Brook for that,” he says.

“To me, the interesting thing about living downtown is the ability to meet strangers, people different from yourself, where everyone’s living in the same neighborhood. The same goes to how you spend your time at night. I want different options, from the very expensive to the cheap. That’s what downtown living is all about, having that diversity.”

For more information about Jefferson Loft Condominiums, visit www.jeffersonloft.com. And visit www.thephoenixbuilding.com for more information about its loft rental apartments.![]()