Birmingham’s Central Business District sits almost entirely in two neighborhoods that wield considerably more power than most people realize. But changes in Downtown’s economic and social landscape could gauge just how well rich and poor, black and white, young and old, can adapt and live together in harmony.

Take Fountain Heights residents, for instance. In a recent neighborhood meeting, they sent Birmingham Housing Authority officials back to the drawing board on four of 25 new houses it’s building as part of the neighborhood’s urban renewal plan. In another meeting, they approved a zoning variance, allowing the Social Security Administration to move ahead on its new $50 million building in their neighborhood.

Take Fountain Heights residents, for instance. In a recent neighborhood meeting, they sent Birmingham Housing Authority officials back to the drawing board on four of 25 new houses it’s building as part of the neighborhood’s urban renewal plan. In another meeting, they approved a zoning variance, allowing the Social Security Administration to move ahead on its new $50 million building in their neighborhood.

Central City residents in a recent meeting torpedoed a neighborhood mart owner’s plans to open a package store, saying it could jeopardize future funding for the brand new Hope VI development. At another meeting, they sent a young entrepreneur home to rethink his proposed liquor-serving pool hall. They worried about the clientele it might attract.

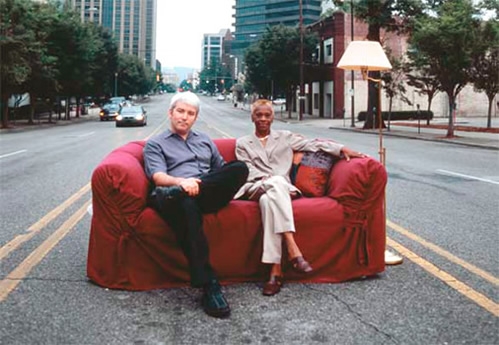

Not that Doris Powell and Jay Taylor let all this go to their heads.

They’re both working to improve the quality of life for residents, using the neighborhoods’ power to approve or block projects that affect their residents.

For Fountain Heights Neighborhood Association President Powell, that means encouraging more housing developments and removing the blight, drugs and crime. It also means sitting at the table when major projects, like variances for a regional federal office building or a new loft development in her section of Downtown, come up for discussion.

For Central City Neighborhood Association President Taylor, that means ensuring that the loft dwellers – who are now the majority of residents – as well as low-income residents fully experience the benefits of revitalization in his section of Downtown.

And together, as president (she) and vice-president (he) of the five-neighborhood Northside Community, they hope to unify residents from a wide array of socio-economic backgrounds for the common good.

“Our goal is to show there is unity in Northside…” Taylor starts.

“Regardless of race,” Powell finishes. “There is no black or white in the Northside community. Simple as that.”

Outspoken Advocate

Doris Powell is a wiry woman, in her 60s, with a voice that crackles with energy and determination.

She has tackled everything from litter to drug dealers to city officials as a neighborhood leader, and public transit and downtown development as a civic leader since moving back to Birmingham in 1998 from the Northeast where was director of sales and community outreach for two Atlantic City hotels and a casino.

Her activism started on the day of her father’s funeral. While her family was mourning his loss inside his Fountain Heights home, someone broke into the garage.

She and about 25 other homeowners on 17th Street North mobilized to look out for each other and clean up the neighborhood. They confronted drug dealing at the infamous “Four Way,” the intersection of 15th Avenue North and 17th Street where the open-air market was so brazen that city police set up a mobile anti-crime unit.

Powell says a Fountain Heights house was among the first shoved to the ground under the Drug Nuisance Abatement Act. The law gave complaining citizens anonymity as protection from vengeful dealers. But she says, “We wanted to appear in court. We wanted them to know us.” The vigilant group of concerned citizens also took City officials to task, insisting that dollars invested in Downtown should also improve the blighted residential area north of Interstate 20/59.

After campaigning on a platform to bring the Fountain Heights Neighborhood Improvement Plan to life, Powell won the neighborhood presidency in 2002 after failing in 2000.

The City of Birmingham’s Community Development Department and the Housing Authority of the Birmingham District (HABD) worked to find appropriate sites in Fountain Heights to build 25 affordable homes.

At the ground-breaking ceremony for the first four houses earlier this year, Jim Fenstermaker, head of Community Development, credited the work of Powell’s predecessors, but he also praised her.

“(She) is a strong advocate for the Fountain Heights Neighborhood, a very hard worker. No one will ever outwork Doris Powell. She has more energy than I will ever have, and she’s a large part of the reason we’re here today.”

But residents balked at HABD’s initial plans for the four houses. Rather than build houses extending down a slope towards an alley, the plan left a small park space behind the houses. Residents nixed the idea, saying the park could attract criminal or mischievous activity. HABD redrew the plans.

Powell is also an active transportation advocate. She is part of several citizen and civic groups that for years have been calling on lawmakers to approve a transit plan, allowing a regional board to draw down $87 million in matching federal funds set aside for construction.

“If my car is in the shop, my sister can drop me off at City Hall and I can walk home in 10 minutes. And I’ve done it in 90 degree heat” she says. “But then you have persons 70, sometimes 80 years old, and they don’t have the capacity to do that. You’re crippling your community.”

Poorest, richest in one area

|

|

The ground-breaking ceremony on four Fountain Heights houses included City and Housing Authority officials, such as Jim Fenstermaker (center), Mayor Bernard Kincaid to his right, and to his left, Councilman Elias Hendricks and Ralph Ruggs. (Right) Powell addresses the gathering of neighborhood residents and officials. |

Fountain Heights – bound on the west by Interstate 65, on the east by 19th Street North and extending from 17th Avenue North to the railroad line to the south – is one of Birmingham’s poorest zip codes. Census figures from 1990 show Fountain Heights’ median family income was half the City’s median income and only a third of Jefferson County’s.

But it also encompasses half of Birmingham’s Central Business District, including the headquarters of the police department, the phone company and the power company. It now includes headquarters of the FBI and other agencies, and will include the new regional offices of the Social Security Administration.

It also includes two of Downtown’s biggest residential loft developments, Jemison Flats and Phoenix Lofts. Soon it will include even bigger ones, such as condominiums planned for the Pizitz department store, the Jefferson Home Furniture, and the Cabana Hotel buildings.

When the incumbent ran in 2004 for the neighborhood presidency, Powell campaigned for votes of loft residents as well as those in her residential base north of I-20/59. Her Central City counterpart, Louise Shufford, did not reach out to loft residents.

Shufford’s traditional residential base was gone, displaced when HABD razed Metropolitan Gardens, the public housing community where Ms. Shufford was also tenant council president, to build its first Hope VI project, now called Park Place.

Most of Central City’s residential base is now in its loft districts, which run east from 19th Street North to the Red Mountain Expressway and south from Third Avenue North to Morris Avenue.

That’s where the new president, 34-year-old Jay Taylor lives.

Shufford, in her 70s, maintains that “someone put him up” to running against her last year, when he brought in his paperwork to run “just minutes” before qualifying ended.

Taylor says nothing could be further from the truth.

When he signed up to run, hours before qualifying ended, no other names were on the list, he says. Nor did anyone encourage him to run against Shufford. Rather, Taylor wanted representation for the loft constituency, who felt their concerns were largely ignored by neighborhood officials.

Bringing People Together

Taylor, a writer by profession, moved back to his native Birmingham three years ago after living abroad six and a half years in places such as Washington, D.C., Minneapolis, San Francisco and Amsterdam. He says he wants to be a part of changing outdated ../images and stereotypes about Birmingham being backwards and racist. “I’m tired of people from other cities looking down their noses at us.”

And being president of one of Birmingham’s most vibrant Downtown neighborhoods is one way to do that.

He campaigned on three issues: securing an enclosed park for dog-owning loft dwellers; creating a database of the 800 loft and other residents to keep them informed and involved in the neighborhood; and unifying its ethnically and socio-economically diverse residents around activities outside monthly meetings.

In addition to new residents in the loft districts and Park Place, Taylor says he’s reached out to former Metropolitan Gardens tenants, some of whom faithfully attend neighborhood meetings. And he has reached out to tenants of Bankhead Towers, a high-rise rental apartment complex for elderly and disabled people, some of whom also attend.

Taylor and his new Central City leadership organized events to bring residents together, such as last year’s Christmas lighting. “Hopefully we can be an example for the entire city. . . I think we’re off to a good start.”

Their most successful event became the 1040 Fest. Taylor and people on the “fun committee,” headed by Leda Dimperio, organized the mini-music festival across from Downtown’s main post office. It encouraged people dropping off last-minute tax returns April 15 (which happened to be on a Friday) to stick around the new neighborhood and visit its stores, bars and restaurants, which offered special prices.

“It was a complete success in showing what our neighborhood could be – diverse, mixed income, extending to all races, ages and socio-economic backgrounds,” Taylor says. “The 1040 Fest got national recognition. And, what I am most proud of, we did it with a zero budget.”

|

Until recently, Central City Neighborhood had one remaining Metropolitan Gardens tenant in its leadership. But Rickey Taylor (no relation to Jay) reluctantly resigned his neighborhood vice presidency after a disagreement with the Housing Authority over his residency at Park Place.

Residents recently chose loft condo owner Camille Spratling to fill the vacant vice presidency. And they picked Toni Leeth to replace Will Johnson, a former assistant to City Councilman Elias Hendricks who resigned as secretary to pursue an MBA.

Now, all of Central City’s neighborhood leaders are loft residents under age 40.

Central City’s boundaries extend east from 19th Street to about 32nd Street, south from Interstate 20/59 toward the railroad tracks. It includes Downtown’s banking centers, the offices of major law firms and the seats of City and County government.

The neighborhood also includes one of the City’s signature skyline buildings and historic landmarks, the City Federal, which is being converted to lofts.

Future Changes

|

Both Jay Taylor and Doris Powell are excited about the new loft condominium and apartment projects springing up across their neighborhoods.

One of them will be the Kessler Building on Third Avenue North that Taylor and his family have bought and are renovating. He, his wife Amy and their dog Bailey will live in one of the planned seven loft units.

Powell and Taylor say loft conversions in the City Federal building on one end of Downtown and the Cabana Hotel on the other will raise depressed property values, add new lights to the City skyline and bring new vitality to their collective Northside Community.

“I think it’s a win-win for all,” Powell says.

http://birminghamview.com/gomepage/member/

<