in 2000, the Birmingham Housing Authority embarked on an experiment that would raze the Metropolitan Gardens public housing project to the ground and seed a new kind of neighborhood using a $35 million federal grant.

After years of protest, speculation, disappointments, disagreements and delays, the new community is finally sprouting out of the ground where the old one used to be, taking shape in the heart of Downtown Birmingham.

In December, new residents slowly began trickling into the first-of-its-kind neighborhood in the City. It’s one specifically engineered for people of all income levels – from public housing residents to college presidents, from corporate leaders to table waiters – to live side-by-side in the same housing development.

It’s part of a federal program called Hope VI.

And it’s no longer Metropolitan Gardens ; from now on, it’s Park Place .

Filling Up Fast

Early indicators suggest Park Place is easily exceeding rather low expectations of a skeptical, mostly suburban, populace who couldn’t fathom that anyone would want to live there, in “dangerous” Downtown Birmingham.

Every one of the 23 townhouses and flats available for rent in Park Place ‘s first phase of development has been spoken for. The apartment managers have a waiting list of people lined up to move into the units as they’re finished.

“I’m very proud to be able to say to those naysayers, ‘I told you so,'” says Ralph Ruggs, the Housing Authority’s executive director, in a mocking voice. ” Park Place has turned into a very strong market.”

According to a prescribed ratio, 40 percent of the units are set aside for public housing residents, primarily for those who lived in the former Metropolitan Gardens . Twenty percent are for working, low-income families, with rents based on income.

The remaining 40 percent are for people who can afford to pay market rate, up to about $980 a month for large three-bedroom units.

Criticism about urban removal – displacing the poor to favor the rich – and about the authority’s overall handling of the public housing residents gave Ruggs many sleepless nights. But he says those worries are behind him now.

With pride, he proclaims that all of the subsidized units are filled with public housing residents; all of the market-rate units have been pre-leased by future Park Place tenants.

Ruggs says some of the 86 Metropolitan Gardens families who wanted to return to the revitalized community have been moved in, after undergoing a screening process by the new managers, Integral Properties. (Its parent company, The Integral Group LLC of Atlanta, is Park Place ‘s principle developer.)

Now that they see the new neighborhood, Ruggs said, some former Metropolitan Gardens residents who chose other housing preferences want in too, but they’ll have a longer wait behind other public housing residents who may qualify to move in ahead of them.

But the majority of ( Metropolitan Gardens ) residents . . . have received Section 8 assistance and that has been their preference for housing. And many of those individuals have indicated they don’t have a desire to return to the revitalized community,” preferring to stay instead in nicer houses with their federal subsidies, Ruggs says.

Urban Transformation

Cathy Sloss-Crenshaw, president of Sloss Real Estate Group which is the co-developer of Park Place , says this project for her company presented a “rare opportunity to take 12 blocks in the center of a major American city and remold it to serve the needs of its citizens.”

The chance to transform an area with the dubious distinction of being located in the nation’s poorest zip code was one the Birmingham real estate maven couldn’t refuse.

In addition to razing and rebuilding the six blocks on which Metropolitan Gardens once stood, Sloss-Crenshaw rallied other stakeholders on the other six blocks to look at the development as a chance to intentionally build a new urban neighborhood.

Part of the new ‘hood includes the YMCA’s transformation of historic Phillips High School gymnasium. It has raised $7 million to turn the relic into a youth development center, with a swimming pool, climbing wall and playing fields.

The new ‘hood will include a new use for a revamped Phillips High. Birmingham School Superintendent Wayman Shiver says the public school system is working with the Annenberg Institute for School Reform to develop a K-8 “best-practices” school there. Teachers there will develop effective learning strategies that can be transplanted at other city schools.

“This project offers the school system an opportunity to work with the community to improve education not only for the children who live here in Park Place, but for children across the entire city,” he says.

AmSouth Bank, one of the largest private, equity investors in the $110 million Hope VI development, owns a drive-through banking center and employee parking lot on one of the 12 blocks. It has bought and demolished an old motel that once stood on the corner of its block.

“We are committed to making sure that whatever future development takes place on that block enhances the Park Place development and that it helps make a stronger Downtown,” says Jeff Gish, AmSouth’s vice president and its corporate community reinvestment manager.

Other components of the new ‘hood include the Rushton Foundation’s urban garden on one block, a museum and culinary arts training center planned for the former Powell Elementary School on one block, and Marconi Park in the midst of it all. Sloss-Crenshaw says plans for the park include installing a landmark water fountain, designed by internationally renowned artist, Kerry James Marshall, a Birmingham native.

” Park Place is already being recognized nationally as a major model for urban revitalization,” she says. “We are creating – and will create – a thriving, mixed-income, mixed-race community in the heart of Birmingham , Alabama . I am honored to be a participant in this effort.”

James Brooks, the Housing Authority’s consultant and project manager for its Hope VI development program, says Park Place is one of the best designed and constructed in the country.

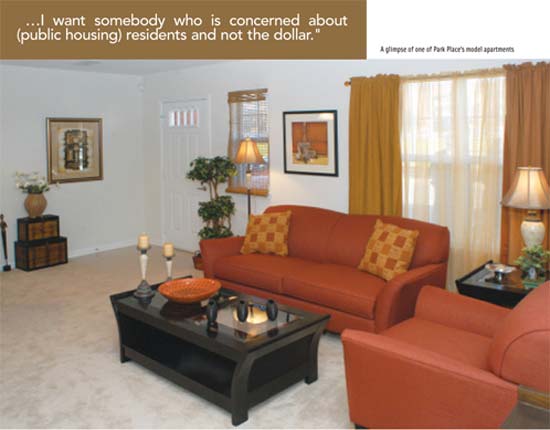

“It doesn’t look like a suburban apartment complex; it has a downtown, urban feel to it, a very strong urban design,” says Brooks a principal of The Boulevard Group. “We intend to submit it for various awards because we think it will win a number of HUD and urban planning and design awards; it’s that good.”

Development Catalyst

Brooks says successful mixed-income Hope VI developments usually spur more private investments, especially in markets where demand for intown housing is strong.

“Over the next several years Birmingham will see a lot of investment on the east side of Downtown,” he says. “I think people look at the amount of investment being made in Park Place . (and that) makes them more comfortable about making investments in those neighborhoods.”

“Over the next several years Birmingham will see a lot of investment on the east side of Downtown,” he says. “I think people look at the amount of investment being made in Park Place . (and that) makes them more comfortable about making investments in those neighborhoods.”

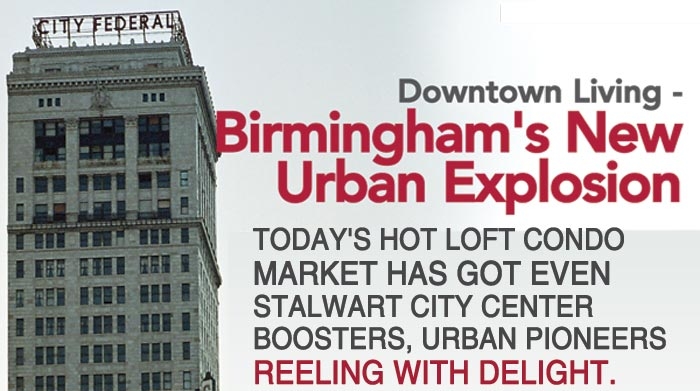

Even before Park Place began taking shape in the blighted northeastern quadrant of Downtown, several private developers announced plans to turn vacant buildings nearby into loft apartments and condominiums, says Michael Calvert , head of Operation New Birmingham (ONB).

He says Ed and Leo Ticheli are building lofts and condominiums in long-vacant Downtown buildings, including the 12-story Stonewall-American Life Insurance building at 23 rd Street and 4 th Avenue North . It’s one of the big, blighted relics that is on ONB’s 12 most wanted list for redevelopment.

Calvert says other loft and commercial projects are filling the gap between the historic loft district area, on Morris Avenue and First Avenue North , and Park Place , which starts on Sixth Avenue North .

“So that the whole east side of Downtown is going to become an urban neighborhood that will have a mixed-use component and have some commercial activity as well as have a real neighborhood feel to it,” Calvert predicts. “Private investment is flowing into that area in a way that I don’t think it would if Metropolitan Gardens was still there.”

Even as workers continue building it, Brooks is confident in calling Birmingham ‘s first Hope VI project a success, along with others in the country.

“Hope VI isn’t an experiment any more,” he declares. “It’s been successful in so many places now. Low-income people are living next to people with higher incomes. You don’t have to look any further than Atlanta to see that it’s successfully done.”

One of Park Place ‘s primary developers, The Integral Group, cut its teeth developing the first Hope VI project in Atlanta , Centennial Place , in 1994.

Using the Atlanta Housing Authority’s Hope VI grant, The Integral Group was the first developer to structure a funding model that blended public monies with private debt and investment dollars to successfully create a mixed-income, mixed-use community.

Atlanta ‘s Housing Authority officials saw its grant as an economic redevelopment tool to build safe, high-quality housing for public housing residents living in the toughest, most economically-depressed areas of downtown Atlanta . The idea was to also make those areas attractive to people who wanted to live downtown and to businesses who could invest there.

Even then, there were strong national critics who said the Hope VI wouldn’t work, Egbert Perry, The Integral Group’s Chairman and CEO, told a group of partners and supporters during the recent groundbreaking ceremony for Park Place .

“The Centennial Place development in Atlanta triggered an additional $1 billion worth of development within six blocks of the site, a site that had no investment for decades and had the highest crime rate in the city,” Perry said. “Today, nobody talks about crime. It’s just a great community. Two years ago, it was announced that a brand new $300 million aquarium and a $200 million museum to Coca Cola would be built near a site that never would have seen that kind of investment.”

Perry predicted the same kind of transformation would happen around Park Place . “I can assure you, without equivocation, that within a few years, we will look back to this development as having been the stimulus for revitalization of this section of the city. And all of you will have had a hand in that.”

What The Future Holds

As with some Hope VI projects, it still isn’t clear that most of the displaced public housing residents, like the hundreds that used to live in what was Metropolitan Gardens , will benefit directly from the project created, presumably, to improve their lives.

Louise Shufford, tenant council president of the former Metropolitan Gardens , calls the new development holy ground. That’s because she and other public housing residents living on the last block of their former community are tenaciously determined to move to Park Place , despite attempts to scare some of them off.

“There are some people involved in this development . . . who had gotten a lot of people to move off this site, even before the development started, with misinformation,” she says, declining to be more specific.

“There are some people involved in this development . . . who had gotten a lot of people to move off this site, even before the development started, with misinformation,” she says, declining to be more specific.

She recounts several incidents: at one time before the new construction, she says someone cut the gas lines under the old buildings, putting remaining residents in harms way; some residents left after men who seemed to work for the Housing Authority told some it would be best for them to leave. They left even after Ruggs himself called to assure them this was not the case.

“Before I moved over here (in December), there were still people going around to different units telling people they weren’t going to come over to this side. But I said, ‘Don’t move. All of us are going to stay here together. We’re going to stand our ground.'”

She says she wants to keep the resident team that kept residents abreast of their rights in the new development “because I want somebody who is concerned about the residents and not the dollar.”

She said public housing residents, especially those residents still living on the last undeveloped block, were supposed to be the first to return to Park Place , “but it hasn’t worked that way and I want to know why.”

Still, Shufford remains positive about the eventual outcome. As long as residents pass criminal background checks and other screenings by the new property managers, they should be able to return. She looks forward to the day when the old public housing residents return to live with new ones in Park Place .

“If things start out right, then they’ll end right,” she says.![]()