Princeton Baptist Medical Center has invested thousands of dollars renovating dilapidated homes in a West End neighborhood. Its investment and the arrival of Filipino nurses are creating interesting results. STORY AND PHOTOGRAPHY BY BY VICKII HOWELL

When most people look at West End , they see an urban community in decline. But when Charlie Faulkner looks from his office window overlooking the Arlington-West End neighborhood, he sees a wealth of untapped potential and opportunity.

He isn’t content just looking. The president of Princeton Baptist Medical Center has pumped thousands of dollars into fixing up dilapidated houses in the mostly forgotten Birmingham neighborhood that surrounds his hospital.

And now, with help from friends, his investments are beginning to reap benefits that could change the course of a community, and the lives of foreign workers who’ve found a place to call home.

It started with the convergence of two ideas: the desire to revitalize West End , and a need to lure talented East Asian nurses to Princeton.

A Plan Comes Together

Like most hospitals in the last few years, Princeton couldn’t find enough local, highly-trained registered nurses and professionals to adequately care for its patients. So the hospital looked for the best help overseas – nurses from the Philippines .

“Philippine nurses have an excellent reputation worldwide,” says hospital nursing director Steve Sherer. They are well-trained, speak English and must pass stringent examinations similar to ones used in the United States , he says.

But changes in already-lengthy immigration laws, especially after 9/11, meant waiting for the nurses for nearly three years.

Meanwhile, Faulkner had been working with Arlington-West End Neighborhood President Keith Aaron to talk about how they could revitalize the community. They were impressed by houses that non-profit developer Frank Dominick of Outreach International was building in the nearby Rising-West Princeton neighborhood.

“We have a program here, that if anybody works here and wants to buy a house in this neighborhood, we’ll pay five percent of the total cost of the house,” Faulkner says. “If they don’t work here,” he pauses, then smiles, “well then, they need to come work here, and then they get the five percent!”

Faulkner collaborated with Aaron and Dominick about buying houses in the areas immediately adjacent to the hospital campus and fixing them up. Faulkner wouldn’t say exactly how much the hospital spent.

But Dominick says the hospital’s money paid for the complete renovation of four houses. One had a roof that was caving in; a family was living in it before Princeton bought it. He says Faulkner wondered if it could even be saved.

“This was not just putting paint on something and calling it new,” Dominick says of the work done on the hospital’s houses. His workers fixed roofs, replaced old water and sewer lines, upgraded old electrical and air systems, and, in some cases, tore out walls to better use space. Three-bedroom houses with one bathroom were converted to have two bathrooms.

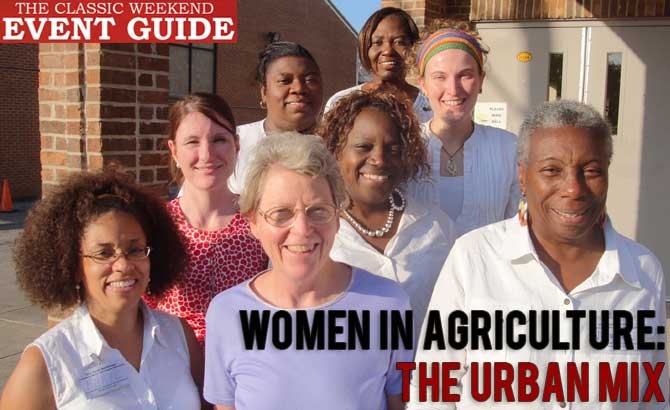

Neighborhood Association president Keith Aaron and some of the Filipino nurses and their families at one of the Princeton Hospital houses.

Faulkner and the hospital “put in the resources to restore the original quality to these homes, when the market would say, ‘This is not a wise investment because the dollars can’t come back.’ . . . It doesn’t make economic sense, but it makes community-impact sense,” Dominick says .

“It takes somebody with the vision to see what the neighborhood can be. The hospital has taken a lead in investing in a way that puts the community, and families who are going to be part of this community, first. And to see what was really blight on the neighborhood – to see the condition some of these houses were in and to see them now – is tremendous,” he says.

The affable Faulkner turns serious and says in a matter-of-fact tone, “We were not happy just fixing a couple of houses. What we want is a neighborhood.”

Then Faulkner got an idea.

“We wanted to do this for the neighborhood but at the same time we needed nurses, so it seemed like a road that came together at the sane time,” he says. “To help these folks new to our country and help them get established, why not put them in a house around the hospital?”

So he struck a deal with the Filipino nurses: if they came to work for Princeton , they could live in the houses near the hospital, rent free, for about a month. Families who didn’t have cars could walk to work, and those living nearby could get there quickly on icy or snowy days.

East In West End

Romeo Albornoz, Esther Bernal, and Aileen Lagman are among the Filipino registered nurses whose families took Faulkner up on his offer. In all, about 10 families of the foreign workers at Princeton live in the houses Dominick restored.

The three said they came to America looking for a chance to hone their patient-care skills as well as find better pay, better technology and better conditions, a place where they have greater security and greater freedoms.

Bernal adds, “The people here are all friendly and supportive. That’s what we like about you Americans. It’s not to flatter you. But I think it’s your nature.”

But more importantly, they have a chance to openly practice their Christianity in a hospital with a faith-based mission. Doing so was dangerous in Saudi Arabia where they’d worked for a time.

“It is very strict. You cannot profess your Christian faith, or they might cut your head off,” Albornoz says. While he had relative ease of freedom going about in Saudi Arabia , his female colleagues did not.

“The males are very dominant, the women are very restricted,” Lagman says. Like Muslim women, she had to cover herself completely, showing no skin, when she went outside. She could not eat in front of Muslims during Ramadan, their month of fasting.

The cultural differences meant that male doctors couldn’t touch females in any way, unless a male guardian or family members were present. “That’s a big thing for them. You could be called by the religious court,” she says. “The restrictions made patient care very difficult.”

But at Princeton , “in spiritual care and aspects of patient care, we can give our best here because we can give 100 percent total care to the patient, without suppression,” she says.

She and the other nurses say they enjoy their freedoms here, and they like living in homes that are so close to their new jobs.

The Filipino nurses who came to Princeton didn’t have to live in West End ; others of their colleagues moved to more affluent areas like Homewood and Crestwood.

But Albornoz said he and the nurses like Bernal and Lagman decided to stay “because of the vision that’s being instilled in us by Mr. Faulkner and the hospital, that they were going to make this community a great community, together with Keith. Those initiatives are enough for us to live here in the community.”

Vision for New West End

Faulkner is taking his idea for Princeton housing further still.

“If we’re going to put together housing for our staff, why would it just be for the Filipino staff? Why couldn’t it be for anybody that really wants to work for us, to get a start, to get on their own feet?” he says. “So (the houses are) not going be just for the Filipino nurses or just for the nurses. It’s going to be for anyone who wants to come here and needs a place to start out, to get back on their feet.”

As usual, one good idea led to another.

“Then we thought, ‘Gee, if we do this for people who travel half way round the world to come work with us, why can’t we do this for people who live in the West End ?” Faulkner says. In addition to the six houses that the hospital owns, Faulkner says it also bought two small apartment units as well.

And Dominick is building four new houses near the hospital. He believes the market for new housing in the area is strong; he easily sold houses in nearby Rising-West Princeton. He says he had as many as 20 pre-qualified residents lined up to buy them.

Faulkner and Aaron believe that by concentrating the new and renovated houses in a defined area near the hospital, they will create a critical mass of interest from people who want to stay in, or even move to, the West End community.

They are starting to see a transformation. Property values are rising around where the new and remodeled houses sit, and they’ve noticed more people in the area are fixing up the exterior of their own houses.

Aaron hopes that the new families, new houses and investments made by Princeton , and nearby stores such as Walgreen’s and Food World, will soon spur economic redevelopment in the mostly vacant businesses along Tuscaloosa Avenue and along Lomb Avenue .

“We want things in West End like everybody else has in their neighborhood. There is not a pizza place or a sit-down restaurant here. That’s a big thing we’re pushing for,” he says.

“The hospital has been a big draw, as well as being the biggest employer on this side of town. We are glad to see a private company like the hospital take the initiative to do housing,” Aaron says. “It gives the neighborhood an injection, and it gives validation to the business community and the work it’s doing.”

The West End community already has a new state-of-the art library. Aaron said the school board plans to build a new $26 million high school in the area. And Faulkner said the city is set to add a lighted walking track near Lomb and Cotton Avenues.

“We want people to see that West End is a great place to live, a great place to work, a great place to walk around in the evening.”