Birmingham is like a ship without a rudder. It turns here then plows through choppy waters there, but it seems headed in no particular direction.

In 1992, the City Council adopted what was then called the Birmingham Comprehensive Plan. It outlined policies and strategies to guide the city’s future for at least 10 to 15 years in areas such as housing, community renewal, transportation, environmental management and the City Center.

Problem is, neither that plan, nor the one completed 30 years before it, guides the daily decisions that the mayor, the council or government officials must make to stay the city’s course. Despite the progress past political leaders have made, the Magic City has still lost much of its luster in the last 40 years. In that time, the city lost almost one-third of its population as whites fled to the suburbs in the ‘60s and ‘70s, followed by middle-income blacks in the ‘90s. With more houses available than buyers, residential property values fell. Scores of city neighborhoods gave way to crime and blight. And its public schools struggle academically to this day.

[Cue the Batman music] Is all hope gone? Does anyone know where Birmingham is headed? Will Birmingham continue its downward spiral and end up singing the Inner-City blues? Will the Magic City get out of its “Why-Can’t-We-Be-Like-Atlanta” funk?

In the past few years, a new generation of elected city, county, and federal leaders have come to power in Birmingham. They come without the political baggage of past administrations. They come promising cooperative attitudes, open-door policies and fresh ideas to political leadership. But can they save Birmingham? Stay tuned.

Mayor Bernard Kincaid at the Helm Again

After winning re-election in November 2003, Kincaid seems born again. He’s not the cantankerous mayor who tangled horns with two groups of City Council colleagues: one that opposed him at every turn in his first two years, and the other that grew increasingly frustrated at their inability to work with him. In fact, four council members ran against him in last year’s mayoral election.

But Kincaid emerged victorious. And (almost) contrite. On election night, he vowed to work cooperatively with the current City Council to move Birmingham forward. He’s since met with them all to discuss concerns for their districts and goals for the city. Economic and community development is now one of the “new” Kincaid administration’s top goals. Kincaid envisions what Birmingham could look like 10 years from today. “I see our civic center being expanded, with a domed stadium,” he says. “I see our having a regional transportation system,” he says, one with park-and-ride lots, high-occupancy vehicle lanes and a City Center circulator or street cars to move people around Downtown.

The mayor envisions the second phase of the intermodal facility completed. There, passengers from MAX and Greyhound buses, Amtrak, and taxi services would converge. At least $2.75 million of the amount needed for the second phase is already in hand, Kincaid says. Just south of that facility, Kincaid sees the Railroad Reservation Park completed in 10 years. The major piece of inner-city green space would allow walkers and cyclists to go from First Avenue South and 14th Street as far as Sloss Furnaces. “Ten years from now, I see the Sears property developed, which would anchor our Entrepreneurial District,” he says. The southwestern corner of Downtown has been designated an incubation district for high-tech and biomedical industries.

If new businesses grow or expand to support biomedical research at the University of Alabama at Birmingham and other institutions, “then all of that spells nothing but economic development for us,” Kincaid says. In the coming decade, the mayor sees an expanded international airport built to carry cargo for more industries attracted to the region. And in that decade, these and other projects will generate tax revenues to help fund one of the city’s most crucial redevelopment pieces – housing for people of all incomes.

“It’s absolutely vital that we develop new housing, redevelop existing housing, stop this demolition by neglect,” Kincaid says. Creating upscale neighborhoods “is the only way we’re going to compete with the suburban areas. Safe, clean streets, living closer to work, protecting the environment – it’s a winning formula.” Kincaid is counting on his administration, as well as the City Council, to set the course for Birmingham’s future (see “Policy Matters,” page 33).

Shelia Smoot on Birmingham’s Side

What successes Birmingham accomplishes on its new vision questwill have to happen in tandem with the area’s other largest government, the Jefferson County Commission. Commissioner Sheila Smoot, the former television reporterwho took office in 2001, oversees community and economic development responsibilities for the county.

She comes with a passion to bring county resources to neglected areas, many of them in Birmingham neighborhoods that she and Commission President Larry Langford represent.

Smoot doesn’t mind using her office as a bully pulpit. she’s preached to developers about the need to build Summit-type shopping centers, restaurants and other amenities, in western Birmingham. she has publicly criticized property owners and managers who run substandard apartments in the City and “encouraged” them to clean up their operations. and she’s courting other new property developers to come with new ideas to refurbish and build new housing in the poorest sections of the county, including the City.

the county took over the Workforce Investment Authority from the City, Smoot says she’s passionate about helping people anywhere who need help. “My duty and my challenge is to help people prosper. Workforce development dollars are there to help capture those displaced workers, the man and woman who didn’t complete high school,” she says, “to help them to be competitive and earn a decent salary for them and their families.” Smoot and her staff recently reshaped the long-standing Workforce Investment Board. It oversees millions in federal job-training dollars across the county for about 3,000 displaced workers, under-educated adults and youth.

At one Workforce Investment board meeting, Smoot says she asked members, “‘How many of you have hired any of my displaced workers or any of my kids?” and nobody could raise their hand. I said, ‘Why are you on this board? If the big boys can’t hire my folks, why are you sitting here?” The board’s new focus, she says, is to prepare disadvantaged citizens for jobs in the health care industry and in biotechnology, two important job growth sectors in the Birmingham area. She has also directed the Jefferson County Economic and Industrial Development Authority to explore building a new county industrial park that would attract biotech businesses to the county.

The County Commission recently set up a $5 million economic stimulus package that’s administered through Operation New Birmingham (ONB), a non-profit group dedicated to revitalizing the City Center. The program extends short-term loans of $100,000 to $1 million (with interest rates around 1%) to businesses and developers who’re starting or expanding their ventures. Smoot wants the program to help a wide spectrum of entrepreneurs and businesses. “So I’ll be monitoring them (ONB) to see not only who gets helped, but also who doesn’t,” she says.

Smoot is also working with Alan Hunter, a former MTV veejay and film producer, to establish a county film commission. Their goal is to recruit Hollywood film crews – and the wads of cash they unload in local economies – to the Birmingham region.

Artur Davis Takes The Initiative

Unlike city and county officials, federal lawmakers don’t have their own pots of money to spend directly in their districts. But U.S. Congressman Artur Davis in 2003 started an economic development process in his 7th Congressional district, which includes many of the state’s poorest counties and economically depressed sections of Birmingham. Initiative 7 brings much-needed technical assistance, some money and other resources to the district.

Mostly, it’s bringing hope. Davis’ Initiative 7 project team of nationally-recognized and local community builders organized meetings with constituents throughout his district last year. Entrepreneurs and community leaders in the Black Belt counties and in Birmingham City dusted off their dreams and business ideas that have lain dormant or on life support for years. They brought them to the Initiative 7 team.

The result is a package of about 34 community-based economic development projects, from expanding a specialty clothing store in Woodlawn, to expanding shrimp farm operations in Lowndes County (see “Profit Margin“).

The projects hold so much potential that Art Campbell, a vice president of the Federal Home Loan Bank of Atlanta, is spearheading efforts to find capital funding or them all. Campbell says his bank, with more than $1 billion in assets, looks for people doing worthy projects that build communities from the ground up. He doesn’t know how much the bank can contribute to Davis’ overall efforts, “but we’re very excited about the opportunity to work with somebody who has put this kind of imagination and thought into it.”

Davis says the Initiative 7 projects “represent the dreams of people who want to better their communities, people who believe they can take the raw materials of their communities and make themselves stronger and better.”

The freshman congressman is exploring another path to bring more help to his district. Last year, Davis coordinated a day-long bus tour of Black Belt industries and innovative economic projects for Mississippi lawyer Pete Johnson, head of the Delta Regional Authority (DRA) and state economic development leaders. DRA serves a 240-county/parish area in an eight-state region, including Alabama. It is designed to remedy the region’s chronic poverty by distributing federal funds and fostering partnerships that stimulate economic development.

Davis introduced the Southern Empowerment and Economic Development (SEED) Act, his first bill, last year. It would extend the DRA’s reach into the Black Belt, which he calls “an undiscovered jewel.” That means more money and technical assistance to support grassroots efforts that improve economic conditions in his district, much like Initiative 7 does.

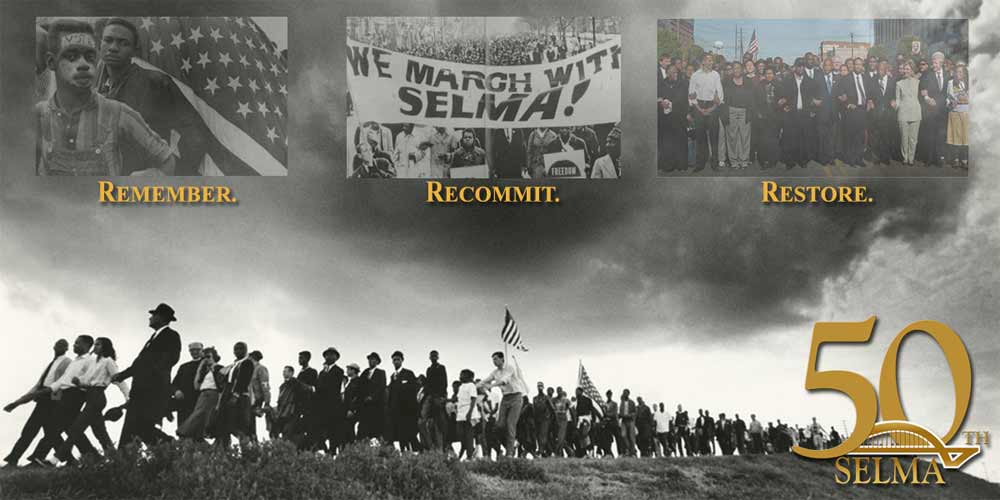

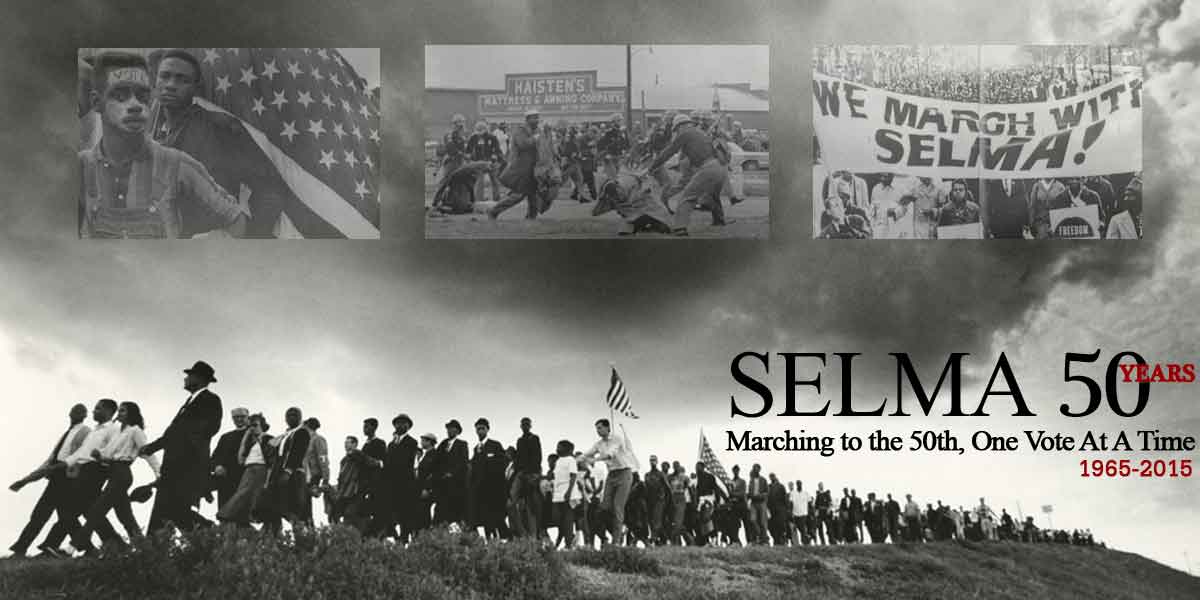

Davis says citizens just need a little boost from responsive government leaders in order to transform their own communities, such as the DRA grants Johnson announced for a sewer system in the City of Pennington in Choctaw County and an airport runway extension in Selma. “We simply have to unlock the door of opportunity, and I’m convinced there are people who will come marching right through them.”![]()