Cathy Sloss-Crenshaw is standing with her back to what just might be the most breathtaking view of Birmingham in the City.

Anniston’s mayor, city councilmen and business owners have gathered at Sloss Real Estate Group, located atop a steep ridge near Red Mountain. They sit in Sloss-Crenshaw’s conference room, where the far wall is made of floor-to-ceiling glass, offering a panoramic view of the Magic City that stretches for miles. In a single glance, one takes in tree-lined neighborhoods, skyscrapers and beetle-sized cars buzzing along the interstates that encircle the city.

But the men and women gathered in Sloss-Crenshaw’s conference room are ignoring the view, concentrating instead on their hostess. Fingers splayed, her hands move rapidly over blocks of an enlarged map of the City Center, as the group of Anniston city leaders look on. They have come to discuss the concepts of urban revitalization, to help create a new vision for their own city and to learn how to carry out that vision with precision and skill.

It’s a subject Sloss-Crenshaw knows a thing or two about.

Revival With Roots

Though she says many things to the Anniston group, the phrase Sloss-Crenshaw repeats most often is “pieces of a puzzle.” It’s clear in the way that she gazes at the map before her that “a puzzle” is exactly what she sees in the computer-generated blocks that represent buildings and land and people.

It’s equally clear – from the enthusiastic way she speaks of rebuilding Birmingham from the inside out – that finding a solution to this puzzle is what most fascinates the developer.

Sloss-Crenshaw speaks of the importance, in a larger sense, of building pathways between Anniston and Birmingham and the mutual rewards for growing together as a single region. That process begins, she explains, by building each city from within in such a way as to create rich, diverse communities.

“You need a clearly-defined downtown,” Sloss-Crenshaw tells the group. “You have to hold onto your history, as we have.”

Revival with roots is the monogram of Sloss-Crenshaw’s resume, and even her personal history. Her great-great grandfather, Col. James W. Sloss, was one of the original barons who ignited the steel boom that put Birmingham on the map. The former railroad man and founder of Sloss Furnace Co. in the early 1880s, recognized Birmingham’s potential in the steel industry, then helped grow it into the “Pittsburgh of the South.”

It is ironic that Birmingham’s well-documented decline of the 1970s came in no small part as the result of a loss of jobs in the steel industry, which had in the century before it, given birth to the “Magic City”. More ironic still, Sloss-Crenshaw has come along a century later to help generate the wave of rebirth that now reverberates throughout Birmingham.

It’s All About People

Sloss-Crenshaw got her start as a developer in the 1980s. An unlikely candidate for the field, she went to work for her father, Pete, armed with a college degree in English and what Michael Calvert calls the instincts of a visionary.

Sloss-Crenshaw got her start as a developer in the 1980s. An unlikely candidate for the field, she went to work for her father, Pete, armed with a college degree in English and what Michael Calvert calls the instincts of a visionary.

“A lot of people have visionary ideas, but she understands the financing, the actual development steps that are needed to make it happen,” Calvert says. “She brings together vision for the community and the City with hard-nosed real estate development expertise.”

Calvert serves as the executive director of Operation New Birmingham (ONB), a non-profit agency devoted to the revitalization of Downtown. In 2003, Sloss-Crenshaw ended her term as chair of the ONB board. During her long tenure on the board, Calvert says, she pushed non-stop to generate growth in the City Center.

“I think she is one of those people who recognizes the importance of the city core,” he says. “The City Center is the heart of the metropolitan area and it’s important to keep that thriving.”

Calvert says Sloss-Crenshaw’s vision is obvious in her very first development project in the Lakeview District, an area that sits on the edge of the City Center. Sloss-Crenshaw took on Lakeview more than 20 years ago, when it was a mostly abandoned, one-time light-manufacturing district.

At the time, he adds, others took one look at the empty lots, the sub-standard housing and the overgrowth choking Lakeview and looked no further. Sloss-Crenshaw took one look and saw an historic relic of the past with the potential to become a testament to the City’s future.

“She has the boldness to try things that others might shy away from. She really sees the highest and best potential for an area and goes after it,” Calvert says. First, developers like Sloss Real Estate and Bayer Properties gave businesses – particularly those on 29th Street South and 7th Avenue South – attractive storefronts in which to operate. Historically relevant details like sidewalks, green space and teardrop-shaped lamp posts were added and preserved. They deliberately planned events, such as the seasonal Pepper Place Farmer’s Market, street fairs and the Shamrock Festival in honor of St. Patrick’s Day – all in an effort to herd people into the area.

Today, Lakeview is a designated design district, the daytime home to Pepper Place and a thriving vein of related merchants, such as architects and interior design firms. When the sun sets, the area is transformed into a hotbed of entertainment options – brightly littered with clubs, restaurants and most importantly, Sloss-Crenshaw insists, people.

“It’s all about people,” she says. “It’s all about bringing them together.” It’s also all about preservation for Sloss-Crenshaw, who chatters excitedly and at length about the bounty of historic buildings, neighborhoods and homes in Birmingham. Though she can’t save them all, she has saved several.

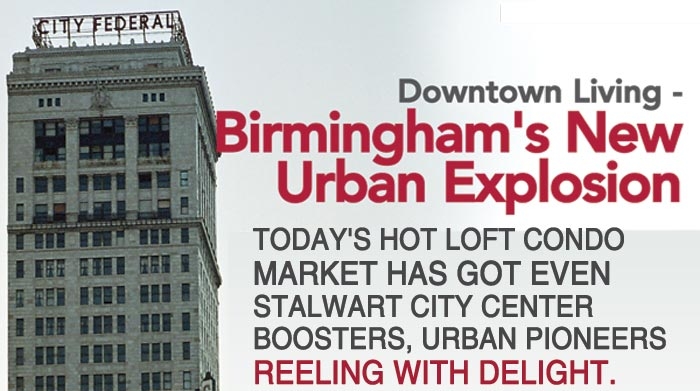

One such rescue is the old Federal Reserve building on 19th Street North. Now an 11-story office tower known as One Federal Place, the building was falling into disrepair and blight when Sloss-Crenshaw got her hands on it. In partnership with an Atlanta development firm, Sloss-Crenshaw funneled more than $50 million into One Federal Place and in doing so, managed to create a downtown centerpiece.

Today, the building is home to such heavyweight tenants as the law firm Bradley, Arant, Rose & White, which occupies six floors of the building. Two restaurants also occupy space in One Federal Place – the upscale Restaurant G and the Greek-flavored eatery Zoë’s. Both serve to not only feed the hungry downtown masses, but also to drive people to a part of town that not so long ago was all but empty after hours.

The Popsicle Index

In the lobby of Sloss Real Estate Group hangs a plaque, hung low and off-handedly on a wall in the reception area. It reads: ‘When you build a thing, you cannot merely build that thing in isolation, but must also repair the world around it.”

In the lobby of Sloss Real Estate Group hangs a plaque, hung low and off-handedly on a wall in the reception area. It reads: ‘When you build a thing, you cannot merely build that thing in isolation, but must also repair the world around it.”

The quote is attributed to “A Pattern Language,” a book Sloss-Crenshaw calls her bible. Written in the 1970s by a group of architects, planners and others, “A Pattern Language” has spawned a website and association of the same name. The basic philosophy is one of “unashamed idealism,” to fight urban sprawl by using available tools to “create beautiful, functional, meaningful places in a living world.” The ultimate goal? To bring together people in the places where they live.

The “Pattern Language” philosophy encourages “patient, piecemeal” urban growth in organic clusters, each cell building on and strengthening the other. The book guides the reader on how to transform and shape the spaces in their homes, blocks, neighborhoods, cities and so on.

“You cluster things together. The whole point is to bring people together and build communities,” Sloss-Crenshaw says. As a developer of such communities, Sloss-Crenshaw uses what she calls the “Popsicle Index” as a guiding principal.

“The popsicle index is when any child can walk safely to a corner store and buy a popsicle,” she says with a grin.

Sloss-Crenshaw is what some call an anomaly, a tough opponent in the arena of business – but one with a conscience and a genuine compassion for others. “I think that’s just who she is; energetic, committed and passionate,” says Leigh Ferguson, director of urban living for Sloss Real Estate.

Revitalizing Downtown

One of Sloss-Crenshaw’s most ambitious developments is also the project that has drawn the most fire, including accusations of “urban removal.”

The site that was once home to Metropolitan Gardens, the City’s biggest public housing complex is now the future home of Birmingham’s first HOPE VI project. The more-than $100 million project combines public and private funds to create a mixed-income residential area in the heart of the City Center. Residents will include public housing tenants, low- to moderate-income families and those who can afford to pay market-rate for housing.

While some, including Sloss-Crenshaw, call plans for HOPE VI a social step ahead for Birmingham, critics snipe that the multi-million dollar development displaces the poor – particularly hundreds of public housing families who were relocated or left before Metropolitan Gardens was razed.

Ferguson counters that the project, renamed Park Place, will help uplift many of those same economically disadvantaged families, while infusing the downtown area with vitality and diversity.

“This isn’t just a pipe dream; there’s still a lot of work to do. This will help create a downtown with a variety of amenities and a lot of economic energies,” Ferguson says. “We see Park Place as a business opportunity and trend of where urban places are headed…a place where people choose to live, where they can enjoy life without the necessity of driving 30 miles a day.”

Once complete, Park Place will include commercial development and more than 600 flats, townhomes, lofts and single-family condos, some for sale and some for rent. People-friendly details such as street-front doorways, porches and community parks, are deliberate additions, intended to draw people together.

“For instance, you put porches on the south side, because people naturally go to the sun,” Sloss-Crenshaw says. “Our challenge is to get people out on the streets, get them moving around.” Park Place, she believes, will do exactly that for the downtown – help rebuild it from the core outward and reverse the suburban sprawl that has, over time, bled the inner city of its life-force.

“When it comes to vision, we need to be very clear about what we’re trying to accomplish,” she says. “We have beautiful, historic housing stock and buildings that are not so far gone that they can’t be brought back. The goal is not to gentrify, but to rebuild communities.”