The relationship between Hollywood and the South has long been tense. Since the days of the first “talkies,” the South has supplied its West Coast sister with a deep well of material and talent. Our Tallulah Bankheads we gladly give. It’s the “material” part that’s been the sticking point.

Less than a decade ago, Forrest Gump exploded onto movieplex screens across America, snagging an historic amount of attention and six Oscars to boot. At the time of its 1994 release, debate raged below the Mason-Dixon about Forrest Gump and its portrayal of the South. Some found the ticklish itch of truth in the film’s syrupy accents and cornpone depictions. Others didn’t – or simply refused to – get the joke.

Either way, the attention of the nation was leveled on Alabama, where the fictional Forrest Gump is set. However, not a single frame of the movie was shot in the state. This, despite the fact that the addled, but fleet-of-foot Forrest attended college at the University of Alabama, where his character played football for Paul “Bear” Bryant and witnessed Gov. George Wallace’s infamous “Stand in the Schoolhouse Door.” The exterior campus scenes for the movie were all shot at the University of South Carolina.

There are people – many right here in the Magic City – determined to see Alabama actually star in the movies it helps make famous.

Putting Alabama on the Map

While still quick to complain that no one in Hollywood “can get our accents right,” many Southerners have wised up financially.

Film production crews – large or small – bring “new money” to a local economy, consuming the products and support services that are staples of the trade. They plunk down dollars on lodging, clothing, groceries, office supplies and a host of other items for sets. Once put into circulation, economists estimate, such “new money” triples its effect throughout the community.

Some here believe that Alabama can and should lead Southern states in soliciting film and movie projects. Birmingham native Alan Hunter is one such believer.

“The potential for the film business to be an economic boost to the state is the same as in any other state,” Hunter says. “If you make it a competitive game and if the people – our leaders here – take it seriously like other states do, you’re talking millions of dollars in business that could be brought into the state via the film business.”

Hunter speaks sitting in the sleek comfort of his downtown Birmingham office in Hunter Films. The production company, which Hunter founded with his brother Hugh, is housed in the belly of WorkPlay, an impressive structure on 23rd Street South that is equal parts office space, nightclub, music recording studio and theater.

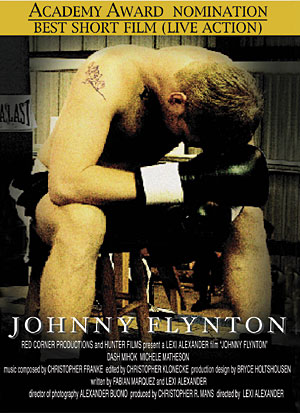

Besides being among the minds that helped create the MTV phenomenon, Hunter is beginning to craft a name for himself in the film industry. An independent short which he helped produce, “Johnny Flynton,” was nominated for an Oscar in 2002, and the Sidewalk Moving Picture Festival he helped found continues to grow in both status and merit.

Currently, Hunter is working closely with Jefferson County Commissioner Shelia Smoot to form a regional film commission to lobby the film industry for statewide projects. Hunter envisions a Birmingham-based hybrid of public and private support.

“Shelia’s really enthusiastic about trying to make it happen. She understands how important it is,” Hunter says. “She’s big into economic development issues and understands probably as well as anyone around here that it is an economic development issue, not an artsy-fartsy one.”

The Birmingham Connection

As commissioner of District 2, Smoot has oversight of community and economic development affairs for the county, as well as roads and transportation. The Michigan native compares an economy with a limited base for expansion to a one-trick pony.

“When it comes to economic development, I don’t believe we should put all of our eggs in one economic basket. I remember well when the automotive plants started to shut down in Flint, Mich., where I was raised and where my father and his friends worked,” Smoot recalls. ”It was devastating, and there was no back-up plan for economic development.”

The commissioner says she supports investing in any venture that keeps the county on the cutting edge economically.

“I want to always be one step ahead of the potential for the loss of jobs and quality of life,” Smoot says. “Lots of industries make money. We need to target more than automotive when it comes to economic development. That’s why I am looking at bio-tech, tourism, transportation and, yes, the film industry.”

Birmingham City Councilman Bert Miller is also willing to roll out the red carpet for Hollywood. Through his Parks, Recreation and Cultural Arts Committee, Miller has named a seven-member board to revive the Birmingham Film Commission. A board that has long lain dormant, Miller believes bringing it back to life will translate into cold, hard cash for the city’s tax base.

Birmingham City Councilman Bert Miller is also willing to roll out the red carpet for Hollywood. Through his Parks, Recreation and Cultural Arts Committee, Miller has named a seven-member board to revive the Birmingham Film Commission. A board that has long lain dormant, Miller believes bringing it back to life will translate into cold, hard cash for the city’s tax base.

“I’m tired of people going to Atlanta to seek out entertainment, to go to auditions,” Miller says. “We want filmmakers to come to Birmingham to use our hotels, use our rental cars, use our restaurants.” Miller adds that his and Smoot’s efforts will dovetail, benefiting not only the city and region, but also the whole state.

“It’s just like an octopus, because with all those arms, everybody’s going to have to work together. This is not about politics. We have to put forth the effort,” Miller says.

Trickle-down Economics

Recruiters in Southern states realize the financial potential of marketing their states to the film industry. Georgia, Tennessee, North and South Carolina and Texas are throwing out big lures to catch the attention of film location crews.

Louisiana, in particular, seems to be leading the pack, aggressively lobbying its legislature for the necessary bait. Hefty legislative incentives stamp government approval on the union of local private enterprise and the movie industry.

Filmmakers are offered a labor tax credit (10 percent of the total aggregate payroll) for employing native Louisianans, while corporate sponsors receive a 10 percent state income tax credit for financially anchoring film projects. If investors sink more than a million dollars into a single project, the credit is raised to 15 percent. Other perks beckoning Hollywood to the bayou include a sales tax exemption and special statewide bulk-rate deals for lodging, a costly element in the filmmaking equation.

Reeling In the “Big Fish”

Alabama recruiters have done their part to attract Hollywood to the land of Dixie. Recent evidence of their success is last month’s release of Big Fish. Directed by Tim Burton, Big Fish is based on the novel of the same name by Alabama native Daniel Wallace. Featuring such high-wattage stars as Jessica Lange, Danny Devito and Albert Finney, Big Fish was filmed last year in the Montgomery area, leaving behind a hefty wad of money in the local economy.

Alabama recruiters have done their part to attract Hollywood to the land of Dixie. Recent evidence of their success is last month’s release of Big Fish. Directed by Tim Burton, Big Fish is based on the novel of the same name by Alabama native Daniel Wallace. Featuring such high-wattage stars as Jessica Lange, Danny Devito and Albert Finney, Big Fish was filmed last year in the Montgomery area, leaving behind a hefty wad of money in the local economy.

That coup came under the leadership of Brian Kurlander. Now living and working in Birmingham, Kurlander was serving as director of the Alabama Film Office (AFO) in Montgomery when he first got wind that Tim Burton was shopping for film locations.

“I’d had it with hearing about movies about Alabama that were filmed in other states,” Kurlanders says, listing Fried Green Tomatoes, Sweet Home Alabama and the aforementioned Forrest Gump as examples.

Kurlander ordered his staff to go home, watch at least two Tim Burton movies and come back the next day with ideas on how to land Big Fish. His team did not disappoint, snagging the scouting crew with what he calls an “intensive” effort.

There’s gold, it turns out, not only in the hills of California, but also in the landscapes of the South. “At every location, they would jump out and put up their camera hands. They would say ‘this is the most picturesque thing I have ever seen in my life’,” Kurlander recalls.

Having lodging and sales tax abatements in place were part of the package that  filmmakers for Big Fish bought into, Kurlander insists. Hunter agrees, but insists that more are needed. “Awareness by a whole lot of people is certainly a good start, but we have to have a couple of governmental officials to make it happen, because until that happens, you’ve got nothing but talk,” Hunter says.

filmmakers for Big Fish bought into, Kurlander insists. Hunter agrees, but insists that more are needed. “Awareness by a whole lot of people is certainly a good start, but we have to have a couple of governmental officials to make it happen, because until that happens, you’ve got nothing but talk,” Hunter says.

The AFO also scored in 2002 with a made-for-television movie about Civil Rights pioneer Rosa Parks. The movie was filmed in Montgomery – where Parks staged her famous “sit-in” on a city bus – and starred actress Angela Bassett and Dexter King as his late father, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

AFO officials are currently chasing projects of varying scales for the state, some in Birmingham. Despite rumors to the contrary, employees insist budget cuts won’t force its doors closed. However, a director still has not been named since Kurlander’s departure last year, and the AFO website button marked “governor’s greetings” remains “under construction.” Hunter says whether the Montgomery office closes or not, Birmingham has the resources necessary to serve as the state’s hub for bringing Hollywood dollars to Alabama.

“There’s never been more momentum about the film business. It doesn’t mean that the film business is active and healthy right now; it means that a lot of people think it’s a groovy damned business to be involved in. They just haven’t quite grasped how to do that,” Hunter says. “At least we’ve started the conversation and the conversation is pretty healthy.” ![]()