Dear Visitor,

This newsletter is bittersweet. I got the chance to see the 21-century movement of our time taking shape in Alabama, the cradle of the modern Civil Rights Movement. That 50-year-old freedom struggle has now expanded to include healthcare, immigration and the LBGTQ community.

But one of my colleagues in arms, Rev. Ronnie Williams, won't be here to see this new movement or the fruits of his labor in the area of public health. However, his life has taught me so much and inspired me personally. He always encouraged me to use the power of my pen and this platform to inspire and motivate us all to remember and care for "the least of these" as well as our society as a whole.

I wrote both of these stories in his honor.

Thanks for reading,

Vickii Howell

Editor-In-Chief

Anatomy of A 21-Century Movement

Moral Monday Movement leader Rev. William Barber II came to Alabama to inspire the state whose people ignited the modern civil rights movement and changed the world.

Rev. Barber has a moral handle on what's right for the people. He's a voice crying in the wilderness. He's six-feet-and-three-inches and 300+ plus pounds of righteous indignation, preaching a message of justice and mercy, of personal responsibility and shared accountability. He understands that the moral arc of the universe is bent toward justice, despite what we feel or see, and that in the end, what's right becomes clear and worth standing for.

And what's right is basic human dignity -- to be treated with respect, to get medical care when it's needed, to make a living wage that allows people to live free and contribute to the good of the order, to vote in a democratic society without unnecessary restrictions, to live in an environment free from harmful pollutants and dangerous conditions, to choose who to love, to live free from danger and discrimination regardless of race, gender, creed or sexual orientation, among other concerns.

These are the basic concepts of the Moral Monday Movement that Rev. Barber has helped galvanize and lead now for seven years in North Carolina. And for these reasons, the Baptist preacher and president of the North Carolina State NAACP has taken a stand. And he's inviting any one of like mind to join him.

In his appearance last week, Rev. Barber shared his vision and the lessons he's learned thus far. "We've come to share some of the practices we've learned that work. If you all take these and move with them, you'll see some powerful results. This is not from what we've heard, but from what we've seen."

He said he didn't come to Alabama to lead the Movement, but to remind its people of the historic role that Alabama has played in the first part of the civil and human rights Movement, from the moment in 1955 when Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on a segregated Montgomery bus to a white man.

"It's your moment. You have to lead this," he said during a prayer breakfast held in the annex of Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, where Dr. Martin Luther King Jr was once the pastor. About 100 people from many organizations around the state including members of NAACP units, people of many races, faiths and cultures listened to him break down the key components of his growing Movement.

"Nobody can come from (Washington) D.C. or New York to lead this because movements begin from Montgomery up, they don't come from DC down. I'm just glad to be an encourager this morning and I'm glad to be a part of this beginning."

The reason the movement has to be based on morality and not race is because this crowd of current-day leaders are so extreme that they are hurting their own people. "You're not just hurting black people. When you deny 400,000 people Medicaid expansion, you're hurting Republicans. You're hurting white people. You're hurting veterans. The more the movement lifts up those facts, Barber said, the more people will be drawn into the cause.

"So that's why a moral movement --- not a left movement, not a right movement, not Democrat or Republican movement but a moral movement -- is needed. You need to pray about that and keep that focus."

The moral center has to come from clergy (many in Alabama have yet to embrace the new movement) who must be willing to take a stand.

"And when you stand, make them arrest you in your vestments." He said one of the officers who arrested the clergy asked in an angry tone why they were coming into the Legislature dressed like that. "We said, 'We're prophets! We're working. We're on call. We're doing pastoral care for the nation." "And when you stand, make them arrest you in your vestments." He said one of the officers who arrested the clergy asked in an angry tone why they were coming into the Legislature dressed like that. "We said, 'We're prophets! We're working. We're on call. We're doing pastoral care for the nation."

This is the affect being arrested in ministerial garb can have on the situation, as Rev. Barber related about one of his arrests:

"One of the arresting officers, when we got on the elevators, he said, 'Man, I'm going to hell.' I said you won't, if you do what's right. By the way, we're fighting for you to get better wages.'

So the elevator doors closed and the other officer pushed the down button. It shook, the doors opened, and we were still right there on the same floor. The guy said, 'I know we're going to hell!' So then, he pushed it again and the doors closed, the elevator shook again, and we were still there. The people starting hollering, 'Let 'em go, let 'em go.'

The officer said, "Rev. Barber, will y'all please let the elevator go down!?' So I turned to one of my friends who is an A.M.E. Zion preacher, and I said, "Talk to Jesus about it.' And he said, 'Jesus, release the elevator!'

The doors closed, the man pushed down, the elevator went down, and the guy said, 'We all going to hell!!!" When we got on the bus, that guy took the cuffs off and everything. And then he marched with us two weeks later."

Rev. Barber said confronting government officials where they do the people's work and facing possible arrests are key components of the Movement. "Go in that Legislature and claim it as the people's house. You built that house; it's your house! Civil disobedience has to be a part of it, because they don't care about rallies," he said.

"They'll watch you rally and keep right on. You've got to be willing to put your bodies on the line."

Another key component of success is the Movement's diversity, that it's more than white verses black . . .

Read More

Click on the image below to watch the video of Dr. Barber's speech at the Alabama State Capitol on Sept. 22, 2014.

A Requiem For Rev. Ronnie Williams: Poverty, Public Health and the Good Fight

Ronnie's health did not permit him to attend the prayer breakfast and rally featuring Dr. Barber. I'm sure he would have been deeply inspired. But Ronnie himself inspired me, and his colleagues will continue to work in his honor.

Reading "Poverty and Public Health," a great article by colleague Mark Kelly in his Weld for Birmingham newspaper, was bittersweet for me.

It made me think of my friend Rev. Ronnie Williams. He should have been in it.

From the time that I met him two years ago, Ronnie began explaining to me the intricate connection between poverty and public health. Now, public health itself is a deep, multi-disciplinary field of preventative medicine. It requires a mind that can connect health with a broad spectrum of social factors, environmental conditions, political decisions and public policies -- the "determinants of health." It's a lot to take in.

For years, Ronnie, a military veteran with a work background  in IT, had immersed himself in this field, particularly as the former executive director for Congregations for Public Health. The community-based nonprofit came together under a grant to the University of Alabama at Birmingham's School of Public Health. He was also instrumental in bringing the Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies' Place Matters initiative to Jefferson County. in IT, had immersed himself in this field, particularly as the former executive director for Congregations for Public Health. The community-based nonprofit came together under a grant to the University of Alabama at Birmingham's School of Public Health. He was also instrumental in bringing the Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies' Place Matters initiative to Jefferson County.

In these capacities, he came to understand that the real root causes of health disparities among the poor, especially African Americans, was the nature of poverty itself.

Ronnie helped me understand that true poverty is not merely about people being too lazy to take care of their health, their schools, their communities. It's about the persistent, negative systemic conditions that create the environment leading to poverty. It's about people who are essentially locked in an "airtight cage of poverty," isolated like islands in a sea of affluence, as Dr. Martin Luther King mentioned in his "Letter from Birmingham Jail." It's about people feeling hopeless and powerless to change the conditions that beset them, like polluting factories, industrial dumps and railroad systems that bring toxic materials into or through their neighborhoods.

These conditions breed a poverty of the mind that leads to poverty of the soul and spills out as the daily dysfunctions we see in Birmingham, in Bessemer and in most other spots where generations of poverty-stricken people live. Then, on top of that, these people are berated, belittled, marginalized, even shot dead as "thugs," because they're seen as threats and worthy of less sympathy than "normal" folk.

Some people have that something extra deep inside that allows them to escape the cage, to rise above their conditions. But they are generally the exceptions to the rule. Studies have shown that the majority of people born into poverty die in poverty. It's for life. And it's getting worse. As a group, African Americans have disproportionately lived well south of wealth/poverty line.

Yet the problems and the disparities persist. Why?

Because most of the entities tasked with fixing poverty aren't attacking the root cause -- systemic economic inequality.

For one thing, the millions of dollars they receive to study and fix poverty aren't typically used to hire poor folk from poverty-stricken communities. Give the bulk of the money as salaries and wages to these folk, who're well acquainted with the needs in their own community and have the best ideas on how to solve their problems. They can then circulate the money they earn back into their own community as they buy goods and services, pay church tithes and donate to smaller community nonprofits, often run by committed but unpaid stalwarts who are also working to end poverty a few folks at a time.

Some of the people who need to be hired -- or even better, empowered with their own grants through their own organizations -- are nascent leaders with workable empowerment plans who have arisen among the people most impacted by poverty. Train them and give them the resources they need to build capacity and to execute their poverty-eradicating plans within their own communities. These plans enable people to help themselves and their families escape the "airtight cage." Their plans should include identifying and training a pipeline of future community leaders.

Execute the plans. Assess the plans. Modify the plans. Execute the modified plans. Repeat this process, often, until generational poverty is gone and general prosperity is the norm.

Unfortunately, Ronnie himself was "poor" in terms of material wealth. He was trying to build his own organization, The Public Health Network Inc. that would give him the platform he needed to address the problems and solutions he saw.

I was one of his board members, and we tried valiantly to make it work. He opened my eyes to the role of public health in my own efforts through Transformation Birmingham to identify and link new organizations rooted in communities of poverty to build capacity and to mutually support each other.

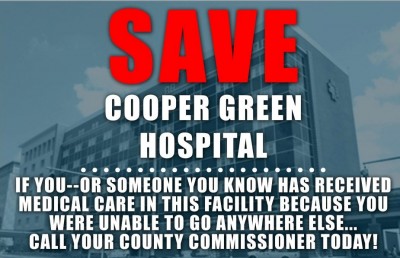

Despite the difficulties, Ronnie never stopped trying. He never stopped working in and for the community. He was never silent when it came to the needs of the poor and his people. He prodded me -- a journalist who prefers working in the background -- to speak up and out about the negative impact the closing of Cooper Green Mercy Hospital on the poor. He encouraged me to keep writing and telling the truth through Birmingham View, to keep building Transformation Birmingham, to keep the faith and continue the good fight.

Read More

|