|

How are the death of Trayvon Martin, the Civil Rights Movement, Black history, crime and education connected? I’m not 100 percent sure, but I’m going to give it a shot, so bear with me please.

I’m thinking back on yesterday as the parents of slain teen Trayvon Martin came to Birmingham, in what was a symbolic nod to our city’s momentous Civil Rights History. It was hard to mistake that as Frank Matthews of the Outcast Voter’s League brought them to speak to a crowd of nearly 100 at the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute and as they stood at the foot of the Martin Luther King, Jr., statue in Kelly Ingram Park. I’m thinking back on yesterday as the parents of slain teen Trayvon Martin came to Birmingham, in what was a symbolic nod to our city’s momentous Civil Rights History. It was hard to mistake that as Frank Matthews of the Outcast Voter’s League brought them to speak to a crowd of nearly 100 at the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute and as they stood at the foot of the Martin Luther King, Jr., statue in Kelly Ingram Park.

The boy’s death at the hand of an overzealous block watch captain in Florida earlier this year has sparked comparisons to Emmett Till, a young black teen who was essentially lynched in 1955 for whistling at a white woman in Mississippi. Till’s horrific death stoked long-simmering resentment among African Americans and was a flash point that jump started the modern Civil Rights Movement as we know it today.

The racial overtone in Martin’s death is also stoking ongoing resentments that African Americans are experiencing in “post-racial America.” They have a persistent problem with the general population’s image and value of blacks in America, where there is blatant disrespect of the first black president, increasing racial profiling by police, and an apparent rising tide of hate crimes aimed at them.

This nagging sense of inferiority – displayed across the media spectrum, in formats from music and movies, to science and technology, from theology and medicine, to art and culture – conveyed in words, pictures and attitudes all say that blacks are not as intelligent, hardworking, beautiful or worthy as other people.

But feelings are not as blatant as cross-burning Ku Klux Klansmen. They are not as easy to identify as is a name-calling police commissioner who sicced police dogs and turn high-powered water hoses on black children protesting non-violently for equal rights. A white man who drags a black man to his death behind his pickup truck can be tried, convicted and executed.

If indeed Trayvon Martin’s death revives themes from the civil and human rights movement for a younger generation, who will the enemies of justice and fairness be? And how will they be defeated? What will the new foot soldiers in this army look like? Who will organize and lead them?

If there are answers to these questions, it would be good for those of us born after 1963 to take a studied, critical look at our history. Truly, if we don’t understand our history to know from whence we’ve come, we could end up making some of the same errors our ancestors made as we move into the future, as Dr. Ben Carson eloquently stated in his speech in Birmingham last week.

I’m convinced that ignorance of American history, particularly Civil Rights history, is to blame for some of the conditions we’re facing. I’m convinced that ignorance of American history, particularly Civil Rights history, is to blame for some of the conditions we’re facing.

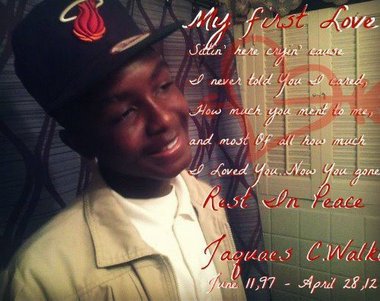

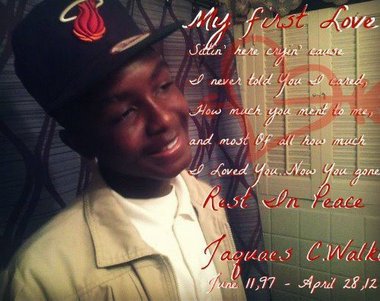

- I think about what seems to be the justified shooting death of 13-year-old Ja'Quares Cortez Walker, who apparently was robbing a couple at gunpoint. Why are the Facebook friends of this deluded child calling him “a soldier,” as if he died in the line of duty? What war was he in? Who was his general and what orders was he following? Did he know ANYTHING about the NON-VIOLENT Foot Soldiers who changed the country and the world without firing a shot? Could a teacher or mentor who knew and valued that history have used it to encourage him or his friends to make different choices?

At the Trayvon Martin town hall meeting at Miles College last evening, several themes kept popping up during the discussion about dealing with racial profiling and crime in the African American community. They centered around self-identity, culture, worth and education. The panelists and audience members seemed to be saying, “Know thyself,” and “True respect starts with understanding who you are, where you come from, and treating others with the respect you want for yourself.”

So much of American history – even world history – excludes the contributions of black people to civilization and culture. I’m trying to learn, but there is SO MUCH I don’t know, despite my college education. And if I don’t know it, I can say with certainty that little Ja'Quares didn’t know it. And I’m almost certain George Zimmerman, Trayvon Martin’s killer, didn’t know it either. Apparently, Zimmerman doesn’t even respect himself, seeing that he essentially dissed his own Hispanic roots with racial epithets on his MySpace page.

As I’ve stated in previous posts, learning history is important for everyone. Until we learn to value all the contributions that all humans have made to the knowledge and wisdom of mankind, we’re doomed to continue the sad cycle of devaluing others and treating them accordingly.

The 50th anniversary of the Birmingham Civil Rights Movement will be upon us next year. This history will attract people from around the nation and the world to the Magic City in 2013. As Birmingham-Southern President Gen. Charles Krulak said in his editorial a few weeks ago, this is history we should embrace.

There is shame and there is pain in it. But there is also power and purpose in it. And within the hundreds of stories among the thousands of participants in that saga, there is reconciliation for past mistakes and help for the problems we face today.

Let’s study our civil and human rights history and learn its lessons, taking the best ideas, strategies and themes from it. Maybe then we can help folks like George Zimmerman value people of color. Maybe black youth can value themselves and the education their forefathers fought to give them, rising above the poverty mindset that robs them of their future. Maybe we can get back to the economic empowerment agenda that Dr. King had set before his assassination. After all, nothing spells success like prosperity.

And we could all use that.

vickii

|