|

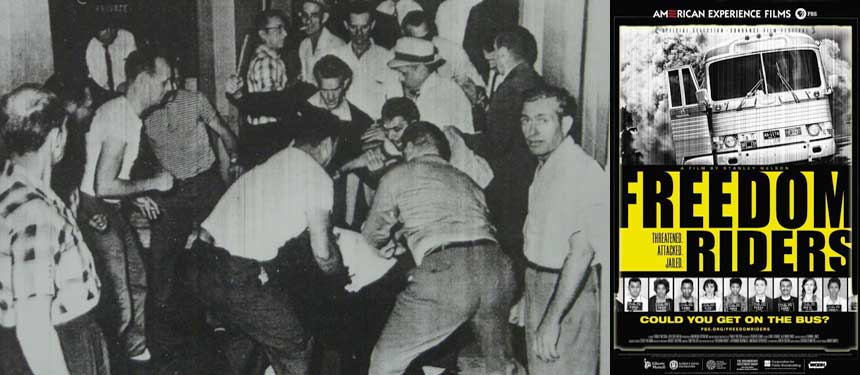

The May 14, 1961, picture of Klansmen savagely beating non-violent Freedom Riders upon their arrival at the Birmingham Trailways bus station helped change the city’s course toward a destiny it has yet to achieve.

By the time the Freedom Riders had arrived in Anniston and later Birmingham, Atlanta and its PR-savvy Mayor William B. Hartsfield told the world that his city was “too busy to hate.” He and other progressive leaders wooed national and international business and industry there by willingly dismantling racial segregation in schools and its downtown stores. As a result or their leadership, Atlanta’s airport was the busiest in the Southeast, and its metro population had nearly double compared to Birmingham’s.

On the other hand, Birmingham leaders squawked bitterly about Yankee reporters whose national stories about racial strife and fear in the Magic City painted a dismal picture that discouraged business growth. They went to great lengths to undo the damage of these reports, except address the real problem – meeting Blacks’ demands to end legal segregation.

In Tokyo, Japan, real estate magnate and staunch segregationist Sydney “Sid” Smyer (then head of the Birmingham Chamber of Commerce) did his best to paint a rosier picture of his city during an International Rotary Club meeting. His attempts went over like a dead rat in the punch bowl once this picture hit the world’s papers. People saw, in black and white, just how far Birmingham was willing to go to maintain a status quo that everyone except Birmingham knew needed to go.

The embarrassing picture forced Smyer and service-based business leaders to challenge the “Consensus,” Birmingham’s ruling class of Big Mule industrial leaders who essentially ran the city, whether they lived within its borders or not. This group of business elites stoked the fires of hatred between racist whites and blacks because it dampened the power of the unions and kept wages artificially low in the local mills and mines. Some of these elites for the most part were caretakers for the larger, out-of-town industrial owners of local plants who benefited by keeping Birmingham’s steel production from ever reaching its full potential and threatening northern cities such as Pittsburgh.

This picture gave a pitifully small group of young progressive professionals the leverage they needed to break the Consensus’ stranglehold on Birmingham’s progress toward racial desegregation and economic prosperity.

These young progressives – including attorneys Charles Morgan and David Vann (who later became mayor) – believed the Consensus leaders had intentionally crippled Birmingham’s prosperity, making it a “one-horse town,” by missing several golden opportunities.

One is the almost urban-mythical story of how these elite leaders turned down Southern Airline’s offer to make Birmingham its southeastern hub in the 1940s. According to the story, the city’s small-thinking leaders believed Birmingham’s airport was big enough for the needs then. But they really feared the international flights could bring in too many folks unwilling to accept the “Southern way of life,” the story goes. The airline company went instead to Atlanta, became part of Delta Airlines, and the rest is history.

Ford Motor Company announced in 1945 its intent to build an auto plant near Atlanta. The young progressives believed that Ford initially considered Birmingham for its location. But the Big Mules and their handlers – fearing a strong union, competitive wages and potential equality among black and white workers would upset the status quo – had let it be known they would not supply Ford with the necessary local materials to make its cars.

In 1949, then-Mayor Cooper Green asked Rheem Manufacturing if it was closing its Birmingham operations because a local steel company had refused to provide the materials for production, as it threatened to do to Ford.

By the time the Freedom Riders rolled into the bus station, Birmingham was already 20 years behind Atlanta. Smyer famously predicted that the incident would give Birmingham “a black eye” for a long time.

Smyer, leading the new coalition of service-based businesses, and the young progressives eventually changed Birmingham’s commission form of government, replacing it with the mayor-council form. This helped them remove Police Commissioner Bull Connor, whose inaction allowed the Freedom Riders fiasco. They were also willing to end Birmingham’s racial apartheid if it meant more economic development. But others, including Connor, were not willing to bend – at all.

It took more black eyes – pictures of police dogs and fire hoses unleashed on non-violent student protestors, and the deaths of four little girls in a church bombing – to make Birmingham finally loosen its kung-fu grip on the poisonous system of racial discrimination.

Fifty years later, Birmingham is still recovering from visionless and corrupt leaders whose decisions deformed its normal growth like a Geisha girl’s bound feet.

Compared to where we used to be, Birmingham has made absolute progress. It took the bold and courageous few like Morgan and Vann, idealistic young adults like the Freedom Riders and the children in the Birmingham movement to get us where we are today. Birmingham’s Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth and Dr. Martin Luther King with Rev. Ralph Abernathy of Atlanta were all young men in the prime of their lives when they galvanized the modern Civil Rights Movement. Their sacrifice and courage helped America remove what native daughter Condoleezza Rice called its “birth defect,” the remaining legacy of slavery.

My hope is that we NEVER forget the terrible price that was paid for this progress. My hope is that you watch the soul-stirring documentary, “Freedom Riders,” which premieres on PBS tonight. My hope is that we remember this history and resolve never to repeat it. The best way to honor the best of our ancestors is to build a better Birmingham on the foundation they laid for us.

We have the power to do this, like we had the power to dream, plan and build Railroad Park, the new symbol of what we can accomplish collectively.

It’s not a matter of “Can we?” as The Birmingham News asks in its new series, “Reinventing Our Community.” It’s a matter of “Will we?” I firmly believe we have more energetic and bright young minds, extremely talented professionals and enough wisdom to welcome best practices from outside our region to build the kind of community we want to have. Rebuilding our tornado-ravaged areas are good places to start.

The Birmingham News is taking questions later today in an online roundtable today from noon to 2 p.m. seeking our thoughts. Take part in it; start discussions among your peers. We now have an unprecedented opportunity to remake Birmingham into the image we want it to become for the next 50 years. What are we waiting for?

Sources referenced in this post:

“The Freedom Ride Riot and Political Reform in Birmingham, 1961-1963,” by Glenn T. Eskew;

“Bear Bryant: Symbol for an Embattled South,” by Andrew Doyle;

Eyes on the Prize: America's Civil Rights Years (1954-1965) – Interview with David J. Vann.

vickii

Also Tonight

Benefit concert for Alabama tornado survivors, courtesy of the John Lennon Educational Bus Tour that's coming to Birmingham. Click on the image below for more information.

|